The Artist's Muse - November 2015

Christies, the art auction business, chose to sell a number of art commodities under the pretext that the works to be sold had an enhanced value as objects inspired by the artist's muse.

The web page quotes Modigliani, whose painting Nu Couché "graces" the webpage for its banner:

The Artist’s Muse:

A Curated Evening Sale

‘When a woman poses for a painter, she gives herself to him.’

— Amedeo Modigliani

DW ran this story on 10/11/2015

Christie's auction house in New York was packed on Monday night as it broke records during a specially curated evening sale titled "The Artist's Muse."

Following a nine-minute bidding war, Italian painter Amedeo Modigliani's "Nu Couche" or "Reclining Nude" fetched $170.4 million (158.46 million euros), breaking the artist's previous record of $71 million.

Jessica Fertig, co-head of the Christie's sale, told reporters prior to the auction that Modigliani's piece "is unquestionably a masterpiece." The painting - produced between 1917 and 1918 - scandalized Paris when it was first exhibited, prompting police to shut down the exhibition.

Why indeed?

"clickbait" at the museum?

"Sexiest show in town?"

Jackie Wullschlager writing for the Financial Times (NOVEMBER 24 2017) asks this question on the opening of the Modigliani exhibition at Tate Modern.

So, who posed for Modigliani?

Laura Cumming writes a review of Modigliani and His Models, a 2009 exhibition at the Royal Academy for the Observer headlined Pretty vacant, and says:

As Jean Cocteau, one of very few sitters Modigliani ever engaged with, tartly observed, each model looks like the next because they all conform to an inner stereotype. This saved Modigliani the bother of acknowledging, still less analysing, the living being who sat before him, and it's what makes these portraits so reamed-out, repetitious and boring.

So, if any of Modigliani's models were to "give herself to him", then what would she have got back in exchange? As Laura Cumming observes:

The revelation of more than 60 Modiglianis in an empty gallery the other day is that they aren't actually susceptible to very much looking. His portraits deflect attention to an amazing degree. His famous women - long, lean and serene - are never more than they seem on the surface. You could have a pleasant enough time at this show and it certainly won't deflate Modigliani's immense popularity.

But if the old question always used to be how such a violent and tormented drunk could have produced such refined compositions, then the new one ought to be whether the life is now propping up the aesthetic reputation.

Hence, one suspects, the Royal Academy's wily concentration on Modigliani's lovers. These included poet Anna Akhmatova before she saw reason and wannabe writer Beatrice Hastings, whom he notoriously used to drag by the hair (though she got back at him with broken chairs). There are several entirely opaque portraits of his dealer's wife and many more of his last mistress, Jeanne Hebuterne, evidently a devoted slave, who threw herself from a high window the night after his death.

The artist's apparent inability to reciprocate, the obsessive reproduction of a stereotype, the negation of the other, a trance-like absorption in reflections of the self, it is all an uncanny "echo" of the Narcissus myth:

Narcissus by Caravaggio depicts Narcissus completely absorbed in the, closed system of a repeated image, and crucially, unaware that he is gazing at his own reflection.

Several versions of the myth have survived from ancient sources. The classic version is by Ovid, found in book 3 of his Metamorphoses (completed 8 AD); this is the story of Echo and Narcissus. One day Narcissus was walking in the woods when Echo, an Oread (mountain nymph) saw him, fell deeply in love, and followed him. Narcissus sensed he was being followed and shouted "Who's there?". Echo repeated "Who's there?" She eventually revealed her identity and attempted to embrace him. He stepped away and told her to leave him alone. She was heartbroken and spent the rest of her life in lonely glens until nothing but an echo sound remained of her. Nemesis (as an aspect of Aphrodite), the goddess of revenge, noticed this behaviour after learning the story and decided to punish Narcissus. Once, during the summer, he was getting thirsty after hunting, and the goddess lured him to a pool where he leaned upon the water and saw himself in the bloom of youth. Narcissus did not realize it was merely his own reflection and fell deeply in love with it, as if it were somebody else. Unable to leave the allure of his image, he eventually realized that his love could not be reciprocated and he melted away from the fire of passion burning inside him, eventually turning into a gold and white flower.

Echo to Modigliani's Narcissus?

Jeanne Hébuterne (6 April 1898 – 26 January 1920) was a French artist best known as the frequent subject and common-law wife of the artist Amedeo Modigliani.

She was introduced to the artistic community in Montparnasse by her brother André Hébuterne, who wanted to become a painter. She met several of the then-starving artists and modeled for Tsuguharu Foujita. Wanting to pursue a career in the arts herself, and with a talent for drawing, she chose to study at the Académie Colarossi, where in the spring of 1917 Hébuterne was introduced to Amedeo Modigliani by the sculptress Chana Orloff, who came with many other artists to take advantage of the Academy's live models. Jeanne began an affair with the charismatic artist, and the two fell deeply in love. She soon moved in with him, despite strong objection from her parents.

After Modigliani and Hébuterne had moved from Paris to Nice on November 29, 1918, she gave birth to a daughter whom they named Jeanne (1918–1984). In May 1919 they returned to Paris with their infant daughter and moved into an apartment on the rue de la Grande Chaumière.

Hébuterne became pregnant again. Modigliani then got engaged to her, but Jeanne's parents were against the marriage, especially because of Modigliani's reputation as an alcoholic and drug user. However, Modigliani officially recognized her daughter as his child. The wedding plans were shattered independently of Jeanne's parents' resistance when Modigliani discovered he had a severe form of tuberculosis. Throughout 1919 Modigliani had been suffering from tuberculous meningitis and his health, made worse by complications brought on by substance abuse, was deteriorating badly.

On 24 January 1920 Modigliani died. Hébuterne's family brought her to their home, but she threw herself out of the fifth-floor apartment window two days after Modigliani's death, killing herself and her unborn child.

Christie's sale of self-portrait by Jeanne Hébuterne Oct. 2018

Ahead of the sale in Paris of a rare self-portrait by the artist, who was Amedeo Modigliani’s lover, specialist Valerie Hess explains why her tragic and premature death robbed the art world of seeing what she could become.

Until she met Modigliani, Hébuterne had been inspired by the artists of the Fauves and Nabis schools. ‘To some extent, she was more experimental than Modigliani. You can see the influence of Matisse in this self-portrait, the daring blue contours on the face and the very flat background,’ says Hess. ‘But what’s most daring is her gaze, looking straight out at the viewer. She is making a statement to assert that she is an artist in her own right.’

Art and anti-Art in 1916 - Momma or Dada?

Guerrilla Girls

Q. What if DADA had been MAMA?

A. The Guerrilla Girls?

Guerrilla Girls according to Wikipedia; is an anonymous group of feminist, female artists devoted to fighting sexism and racism within the art world. The group formed in New York City in 1985 with the mission of bringing gender and racial inequality into focus within the greater arts community. The group employs culture jamming in the form of posters, books, billboards, and public appearances to expose discrimination and corruption. To remain anonymous, members don gorilla masks and use pseudonyms that refer to deceased female artists. According to GG1, identities are concealed because issues matter more than individual identities, "[M]ainly, we wanted the focus to be on the issues, not on our personalities or our own work."

. . . and according to the Guerrilla Girls:

The Guerrilla Girls are feminist activist artists. Over 55 people have been members over the years, some for weeks, some for decades. Our anonymity keeps the focus on the issues, and away from who we might be. We wear gorilla masks in public and use facts, humor and outrageous visuals to expose gender and ethnic bias as well as corruption in politics, art, film, and pop culture. We undermine the idea of a mainstream narrative by revealing the understory, the subtext, the overlooked, and the downright unfair. We believe in an intersectional feminism that fights discrimination and supports human rights for all people and all genders. We have done over 100 street projects, posters and stickers all over the world, including New York, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Mexico City, Istanbul, London, Bilbao, Rotterdam, and Shanghai, to name just a few. We also do projects and exhibitions at museums, attacking them for their bad behavior and discriminatory practices right on their own walls, including our 2015 stealth projection about income inequality and the super rich hijacking art on the façade of the Whitney Museum in New York. Our retrospectives in Bilbao and Madrid, Guerrilla Girls 1985-2015, and our US traveling exhibition, Guerrilla Girls: Not Ready To Make Nice, have attracted thousands. We could be anyone. We are everywhere. What’s next? More creative complaining!!

There is a use value in "pretending", if it helps us understand a little more about this world of ours (or theirs?), but there was NO MAMA, just DADA!

The Guerrilla Girls: 30 years of punking art world sexism

When it comes to those women artists crucial to the production of the anti-art of Dada, and the art of Surrealism, then we can find multiple revisionist histories, that, although not conducted on an "industrial" scale, are part of an art world industry with its particular vested interests. And buying and selling artworks.

These interests are the interests of billionaires. The vested interests of an academic world, art institutions and museums, tend to steer well clear of socially engaged activism in the here and now, unless the activism has proven "provenance", a track record, is a "bona fide" subject of study, or the result of an original research question. There is a safety in distance, and the distance of time.

THE 8

A BMW "model", plus eight women artists!

The Artsy website generates revenues from advertising, including this banner ad for a top of the range BMW. Underneath this banner we find a revisionist article on the art historical significance of a number of women artists associated with Dada by Meredith Mendelsohn (Aug 14, 2017):

The Women of Dada, from Hannah Höch to Beatrice Wood

No. 1 - Hannah Höch

Da-Dandy 1919

No. 8 - Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

God 1917

Meredith Mendelsohn's copy for No. 8, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven:

Fusing art and life was one of the guiding principles of Dada, and von Freytag-Loringhoven did it with flair. A German-born fixture of New York’s downtown scene in the late 1910s and early ’20s, the fearless and eccentric Baroness made assemblage art and collages, and wrote poetry, as well as modeling and performing. But she might have been most famous for her bizarre getups. On any given day, she might have been wearing a soup-can bra or a hat decorated with dangling spoons or feathers—like a sort of streetwise flapper gone mad. Or she might have been semi-nude, a crime for which she was arrested multiple times.

Flapper gone mad?

Photo of "Fountain" at Alfred Stieglitz's studio, and the photo published in The Blind Man.

Well, in 1917 this "flapper" created "God", out of the "U bend", and it is likely that she also helped create the "Fountain" of all "readymades"!

Fountain, a porcelain urinal signed "R.Mutt". In April 1917, an ordinary piece of plumbing was submitted for an exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, the inaugural exhibition by the Society to be staged at The Grand Central Palace in New York. In Duchamp's presentation, the urinal's orientation was altered from its usual positioning.

Fountain was not rejected by the committee, since Society rules stated that all works would be accepted from artists who paid the fee, but the work was never placed in the show area. Following that removal, Fountain was photographed at Alfred Stieglitz's studio, and the photo published in The Blind Man. The original has been lost.

"R.Mutt" has been taken to be the pseudonym of Marcel Duchamp, and who has thus been credited with a work that has been regarded by art historians and theorists of the avant-garde as a major landmark in 20th-century art. Sixteen replicas were commissioned from Duchamp in the 1950s and 1960s and made to his approval.

However, some have contested that Duchamp created Fountain, but rather assisted in submitting the piece to the Society of Independent Artists for a female friend. In a letter dated 11 April 1917 Duchamp wrote to his sister Suzanne: "Une de mes amies sous un pseudonyme masculin, Richard Mutt, avait envoyé une pissotière en porcelaine comme sculpture" ("One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.")

Duchamp never identified his female friend, but three candidates have been proposed: an early appearance of Duchamp's female alter ego Rrose Sélavy; the Dadaist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven; or Louise Norton (a Dada poet later married to the avant-garde French composer Edgard Varèse), who contributed an essay to The Blind Man discussing Fountain, and whose address is partially discernible on the paper entry ticket in the Stieglitz photograph.

On one hand, the fact that Duchamp wrote 'sent' not 'made', does not indicate that someone else created the work. Furthermore, there is no documentary or testimonial evidence that suggests von Freytag created Fountain.

On the other hand, more recent research has uncovered a New York Article Evening Herald article that claims Fountain was sent into the exhibition from Philadelphia which was where Freytag-Loringhoven was living during this period. Consider the work by Freytag-Loringhoven "God", also created in that same year.

Marcel Duchamp arrived in the United States less than two years prior to the creation of Fountain and had become involved with Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Beatrice Wood amongst others in the creation of an anti-rational, anti-art, proto-Dada cultural movement in New York City.

The Wikipedia article on Dada quotes David Hopkins A Companion to Dada and Surrealism:

The creations of Duchamp, Picabia, Man Ray, and others between 1915 and 1917 eluded the term Dada at the time, and "New York Dada" came to be seen as a post facto invention of Duchamp. At the outset of the 1920s the term Dada flourished in Europe with the help of Duchamp and Picabia, who had both returned from New York. Notwithstanding, Dadaists such as Tzara and Richter claimed European precedence. Art historian David Hopkins notes:

Ironically, though, Duchamp's late activities in New York, along with the machinations of Picabia, re-cast Dada's history. Dada's European chroniclers—primarily Richter, Tzara, and Huelsenbeck—would eventually become preoccupied with establishing the pre-eminence of Zurich and Berlin at the foundations of Dada, but it proved to be Duchamp who was most strategically brilliant in manipulating the genealogy of this avant-garde formation, deftly turning New York Dada from a late-comer into an originating force.

(Hopkins, David, A Companion to Dada and Surrealism, Volume 10 of Blackwell Companions to Art History, John Wiley & Sons, 2016, p. 83)

In the Wikipedia article on New York Dada the only woman artist mentioned is Beatrice Wood, the American artist and studio potter who became involved in the Avant Garde movement in the United States; she founded and edited The Blind Man magazine in New York City with Marcel Duchamp and writer Henri-Pierre Roché in 1917. She had earlier studied art and theater in Paris, and was working in New York as an actress. Wood was characterized as the "Mama of Dada."

Flapper gone mad II?

But what about Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the woman who created "God"?

What if?

When an Afro-Cuban, Chicago-based painter, Harmonia Rosales, painted her own version of Michelangelo’s work in 2017, reimagining God and the First Man as black women, she received a huge backlash.

Ariana Grande

God is a woman . . .

The artist and the model

more "clickbait"?

In the summer of 1943 in occupied France, a famous sculptor, tired of life, finds a desire to return to work with the arrival of a young Spanish woman who has escaped from a refugee camp and becomes his muse.

"Muse", a male projection?

The artist's model is NOT a "muse"!

From the graphic novel Kiki de Montparnasse - Words by José-Louis Bocquet - Art by Catel Muller.

Kiki? Violin? A "Man Ray"? "clickbait"?

Up front . . .

. . . and backPicnic 1937 (Nusch Eluard, Paul Eluard, Roland Penrose, Man Ray, Ady Fidelin) photo by Lee Miller.

Elizabeth "Lee" Miller, Lady Penrose (April 23, 1907 – July 21, 1977), was an American photographer and photojournalist. She was a fashion model in New York City in the 1920s. Miller's father had introduced her to photography at an early age, and she was his model, taking many stereoscopic photographs of his nude teenage daughter. Aged 19 she nearly stepped in front of a car on a Manhattan street but was prevented by Condé Nast, the publisher of Vogue. This incident helped launch her modeling career; she appeared illustrated in a blue hat and pearls in a drawing by George Lepape on the cover of the Vogue edition of March 15, 1927. Miller's look was exactly what Vogue's then editor-in-chief Edna Woolman Chase was looking for to represent the emerging idea of the "modern girl."

In 1929, Miller traveled to Paris with the intention of apprenticing herself to the surrealist artist and photographer Man Ray. Although, at first, he insisted that he did not take students, Miller soon became his model and collaborator (announcing to him, "I'm your new student"), as well as his lover and muse.

While she was in Paris, she began her own photographic studio, often taking over Ray's fashion assignments to enable him to concentrate on his painting. So closely did they collaborate that photographs taken by Miller during this period are credited to Ray. Together with Ray, she rediscovered the photographic technique of solarisation, through an accident variously described, with one of Miller's accounts involving a mouse running over her foot, causing her to switch on the light in mid-development.

The couple made the technique a distinctive visual signature, with examples being Ray's solarised portrait of Miller taken in Paris circa 1930, and Miller's portraits of fellow Surrealist Meret Oppenheim (1930).

Not only does solarisation fit the Surrealist principle of unconscious accident being integral to art, it evokes the style's appeal to the irrational or paradoxical in combining polar opposites of positive and negative; Mark Haworth-Booth describes solarisation as "a perfect Surrealist medium in which positive and negative occur simultaneously, as if in a dream".

Amongst Miller's circle of friends including Pablo Picasso, were fellow Surrealists Paul Éluard, and Jean Cocteau, who was so mesmerized by Miller's beauty that he coated her in butter and transformed her into a plaster cast of a classical statue for his film, The Blood of a Poet (1930).

The Blood of A Poet from UMSchoolOfCommunication on Vimeo.

The subject of Miller's photograph of a Picnic includes Nusch Eluard and Ady Fidelin "topless", while Paul Eluard, Roland Penrose and Man Ray remain fully clothed. When Miller took the photo was she topless too?

However, the substantive subject of Picnic is also dealt with in the cover of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brother's comic, the provoking, but always fascinating painting by Edouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass). Questions remain: What is this painting all about? What is its purpose? Does it have a purpose? The work has instigated many different responses from the many generations of viewers who have engaged with its ambiguities.

NOT "clickbait"?

Coat stand? or clothes horse? or Porte manteau?

Man Ray

Man Ray befriended Marcel Duchamp in New York, where he was influenced by the avant-garde practices of European contemporary artists he was introduced to at the 1913 Armory Show and in visits to Alfred Stieglitz's "291" art gallery. Like Duchamp, he "created" readymades—ordinary objects that are selected and modified. His Gift readymade (1921) is a flatiron with metal tacks attached to the bottom, and Enigma of Isidore Ducasse is an unseen object (a sewing machine) wrapped in cloth and tied with cord.

The first Surrealist work, according to the Pope of Surrealism, André Breton, was Les Chants de Maldoror; written and published between 1868 and 1869 by the Comte de Lautréamont, the nom de plume of the Uruguayan-born French writer Isidore Lucien Ducasse. The work concerns the misanthropic, misotheistic character of Maldoror, a figure of evil who has renounced conventional morality. The Surrealists revived interest in Isidore Ducasse, and in particular for the line from Les Chants de Maldoror;

"beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella"

Mannequins, flat irons, sewing machines, needles, pins, threads, swatches of fabric, and other items related to tailoring appear in almost every medium of his work. These tools are redolent of his family environment. Man Ray's father worked in a garment factory and ran a small tailoring business out of the family home. He enlisted his children to assist him from an early age. Man Ray's mother enjoyed designing the family's clothes and inventing patchwork items from scraps of fabric. Man Ray wished to disassociate himself from his family background, but their tailoring left an enduring mark on his art.

As a renowned fashion and portrait photographer Man Ray used the method of surreal juxtaposition, including the use of "found objects" and situations, to create a symbolically rich modern environment for haute couture.

Created in 1920, Man Ray’s Coat Stand is among his most important Dada works. Featuring a hybrid creation that is half-human, half-machine, like many Dada works, it is a morbid critique of the atrocities of the Great War. When the photograph was first published in 1921, under the title “Dadaphoto” in the single issue of Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray’s magazine New York Dada, a postage stamp preserved the model’s modesty. A small area of emulsion come off when the stamp was removed, visible in almost every known print of Coat Stand including the present example.

Arturo Schwarz described the work as follows:“Man Ray positioned a model wearing only a black stocking on her right leg behind a flat articulated coat stand. The body of Coat Stand was thus provided by Man Ray … the contrast between the nude and the robot-like coat-stand produced a startling effect. Man Ray then photographed this first example of Body Art combined with a Readymade.” (Man Ray: The Rigour of Imagination. Arturo Schwarz. Rizzoli, New York, 1977, p. 160)

Artsy have a review of a Bettina Buck show at the Rokeby Gallery headlined:

Bettina Buck Shuffles through a Museum and Smashes Art-Historical Narratives

Upon entering Bettina Buck’s current show at Rokeby Gallery, the first encounter is with a video, Another Interlude (2015), in which the artist drags a two-meter-high block of foam through the columns, cornices, and canvases of the 19th- and 20th-century galleries of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome.

We pass recognizable paintings, such as Monet’s Ninfee Rosa (1897-1899), and famous avant-garde, experimental pieces, like Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913) and Man Ray’s The Coat-Stand (Porte manteau) (1920). Quickly, the works of art begin to mimic the foam block lugged around by the artist; Rodin’s The Age of Bronze (1877) and Gilberto Zorio’s Column (1967) become versions of the upright phallus in a discipline dominated by males.

The journey that Buck embarks on is as strenuous as it is whimsical. Her feminist narratives are subtle but omnipresent: the block of foam is coerced through the imperial architecture of the museum with a red string tied around it, recalling the one given to Theseus by the princess Ariadne, which led him out of the labyrinth. Moreover, the prosaic nature of the foam amid the hardwood floors and gold frames of the gallery imbues the film with a smug intelligence. Buck, dressed in jeans and sneakers, becomes a totem of the new narrative, a symbol of art now.

Bettina Buck recreates Man Ray's Porte manteau

When we leave the room, we are still there. Buck, in a post-Sherrie Levine move, recreates Man Ray’s Porte manteau (1920) in the gallery space. Her version has the slightest discrepancies: the left leg dons the stocking, rather than the right; the shadows of the scrim in Buck’s studio are much sharper; a marble object resembling a breast replaces one of the living ones, we notice a glimmer of a face behind the cutout. The figure is Buck, a self-portrait with play and poise. As if it were a visual portmanteau, she and Man Ray blend history and the present, the object and the subject, this moment, that picture.

Catechresis - something to make YOU think?

A catechresis involves the creation of a deliberate discrepancy, or discrepancies, in order to provoke the asking, and consideration, of why it is these discrepancies have been presented. Such questions instigate a consciously interpretive activity.

The apparently small differences identified between the Man Ray Porte manteau and Buck's version, make all the difference. A coat stand has become a person, a self-portrait of the artist, even!

Man Ray's original involves a person becoming de-personalized as part of a coat stand, or the "idea" of a coat stand.

Bettina Buck's work, if we look, if we compare, draws our attention to Man Ray's Dadaist "clickbait" tactic, and the presentation of the body of a woman as merely a part of an object and its process of assembly.

The Mechanical Bride. Even!

Subversive, activist, feminist "clickbait"?

The Conversation

Why is the advertising industry still promoting violence against women? September 13, 2016

Misogyny manifests in numerous ways, including social exclusion, sex discrimination, hostility, androcentrism, patriarchy, male privilege, belittling of women, disenfranchisement of women, violence against women, and sexual objectification. Misogyny can be found within sacred texts of religions, mythologies, and Western philosophy and Eastern philosophy.Wikipedia's article on misogyny has a section on Online misogyny:

Misogynistic rhetoric is prevalent online and has grown rhetorically more aggressive. The public debate over gender-based attacks has increased significantly, leading to calls for policy interventions and better responses by social networks like Facebook and Twitter.

A 2016 study conducted by the think tank Demos concluded that 50% of all misogynistic tweets on Twitter come from women themselves.

Most targets are women who are visible in the public sphere, women who speak out about the threats they receive, and women who are perceived to be associated with feminism or feminist gains. Authors of misogynistic messages are usually anonymous or otherwise difficult to identify. Their rhetoric involves misogynistic epithets and graphic and sexualized imagery, centers on the women's physical appearance, and prescribes sexual violence as a corrective for the targeted women.

The insults and threats directed at different women tend to be very similar. Sady Doyle who has been the target of online threats noted the "overwhelmingly impersonal, repetitive, stereotyped quality" of the abuse, the fact that "all of us are being called the same things, in the same tone".

In the Wikipedia article on The exploitation of women in mass media, there is a section on advertsising that ends with a paragraph on the trend in fashion advertsising of representing women as victims.

"Another trend that has been studied in advertising is the victimization of women. A study conducted in 2008 found that women were represented as victims in 9.51% of the advertisements they were present in. Separate examination by subcategory found that the highest frequency of this is in women's fashion magazines where 16.57% of the ads featuring women present them as victims."

Which leads effortlessly to the way advertising is enmeshed in sexual objectification.

. . . and patriarchy!

In the Wikipedia article on patriarchy the section on Feminist Theory and patriarchy references the work of interactive systems theorists Iris Marion Young and Heidi Hartmann who theorize how it is that patriarchy and capitalism interact together to oppress women.

Young, Hartmann, and other socialist and Marxist feminists use the terms patriarchal capitalism or capitalist patriarchy to describe the interactive relationship of capitalism and patriarchy in producing and reproducing the oppression of women. According to Hartmann, the term patriarchy redirects the focus of oppression from the labour division to a moral and political responsibility liable directly to men as a gender. In its being both systematic and universal, therefore, the concept of patriarchy represents an adaptation of the Marxist concept of class and class struggle.

Audre Lorde, an African American feminist writer and theorist, believed that racism and patriarchy were intertwined systems of oppression. In her essay "The Erotic as Power", written in 1978 and collected in Sister Outsider, Lorde theorizes the Erotic as a site of power for women only when they learn to release it from its suppression and embrace it. She proposes that the Erotic needs to be explored and experienced wholeheartedly, because it exists not only in reference to sexuality and the sexual, but also as a feeling of enjoyment, love, and thrill that is felt towards any task or experience that satisfies women in their lives, be it reading a book or loving one's job. She dismisses "the false belief that only by the suppression of the erotic within our lives and consciousness can women be truly strong. But that strength is illusory, for it is fashioned within the context of male models of power." She explains how patriarchal society has misnamed it and used it against women, causing women to fear it. Women also fear it because the erotic is powerful and a deep feeling. Women must share each other's power rather than use it without consent, which is abuse. They should do it as a method to connect everyone in their differences and similarities. Utilizing the erotic as power allows women to use their knowledge and power to face the issues of racism, patriarchy, and our anti-erotic society.

Self-objectification - becoming your own "muse"?

Ben Agger, the author of Oversharing: Presentations of Self in the Internet Age, told the Straight by phone for the article Putting selfies under a feminist lens:

“It’s the male gaze gone viral.” According to the professor of sociology and humanities at the University of Texas at Arlington, the selfie trend is about women “trying to stake a claim in the dating and mating market” with the knowledge that, in order to do so, they must objectify themselves. Agger notices this happening, in particular, on dating sites, where “women realize that there is a photographic traffic in bodies.”

The "selfie" as "clickbait"?

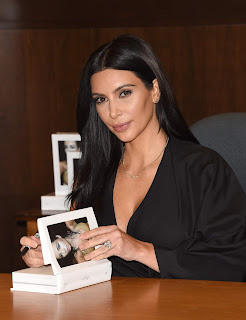

The queen of selfies has officially returned!Following a brief hiatus from social media after she was robbed at gunpoint in Paris last October, Kim Kardashian is back and better than ever— and her first selfie of 2017 is proof. Taking to Snapchat on Wednesday evening, the reality star shared a sweet snap in the car with her mother Kris Jenner, captioning the photo, "First selfie of 2017 with my mama." In the photo, Kim flashes a peace sign and rocks her new lip ring, while her mom smiles in the background.

Selfish is a coffee table photobook written by television personality Kim Kardashian.

It was released on May 5, 2015 by the Universe imprint of the art bookseller Rizzoli. The book features Kardashian's personal selfies, collecting various images previously posted on Kardashian's social media accounts.

According to the Wikipedia article the photobook received positive reviews from critics.

The Selfie; "the male gaze gone viral", sociologist Ben Agger.

" . . . the idea to assemble a book from selfies first came to Kardashian when she was thinking of what to give to her husband Kanye West as a Valentine's Day gift. "I couldn't think of what to get Kanye and so I was like, 'All guys love it when a girl sends them sexy pics'."

Laura Bennett wrote a positive review of the book for Slate and described the book as "insane project, a document of mind-blowing vanity and deranged perseverance". Bennett further accentuated the book's format, and said: "You could call Selfish a sneakily feminist document, an act of reclamation by one of the world's most photographed women".

This article by Jonathan Jones in The Guardian takes a balanced rather than a postive position, verging on the dismissive, even.

He considers that the photobook is "the ultimate slap in the face for anyone who ever pointed a camera with high hopes of being the new Henri Cartier-Bresson or Don McCullin" and suggested that "Kardashian’s selfie-taking is, in reality, a sustained act of self-exploitation in which she sells herself as commodified, leered-at flesh."

Cartier-Bresson and McCullin are, of course, male exemplars of the "art". Jones bemoans the loss of an aesthetic related to photography that the "selfie" replaces. "The selfie marks the end of the age when people thought photographs could be refined works of art, and Selfish is the final gravemarker of that aesthetic delusion." In comparison to the general critical coverage of Selfish on the internet, it is this Guardian article that includes images that are almost examples of a slut-shaming "clickbait" culture.

What Kardashian looks like with sunburn.

Kim Kardashian takes a selfie of her behind.

Jones comes round at the finish:

"The selfie gives an illusion of intimacy that is priceless in an age that cherishes authenticity and reality. It may well be pornographic and objectifying but because Kardashian herself controls what we see, her art seems both honest and, for her, empowering. So come on in, buy the book and be part of her world. Up close and curvy."

It's complicated . . .

Author of Slut! Growing Up Female with a Bad Reputation, Leora Tanenbaum writes:

A teenage girl today is caught in an impossible situation. She has to project a sexy image and embrace, to some extent, a 'slutty' identity. Otherwise, she risks being mocked as an irrelevant prude. But if her peers decide she has crossed an invisible, constantly shifting boundary and has become too 'slutty,' she loses all credibility. Even if she was coerced into sex, her identity and reputation are taken from her. Indeed, the power to tell her own story is wrested from her.

How the Light Gets In: Notes on the Female Gaze and Selfie Culture

By: Mary McGill , May 1, 2018

Note No. 5.

Narcissism, Simone de Beauvoir (2011 [1949]: 667) wrote, is regarded as ‘the fundamental attitude of all women.’ Quantitative studies from around the world illustrating women’s proclivity for selfie-taking seem to underscore this observation, but the reality is more complex. De Beauvoir asserts that what often appears as narcissistic behaviour in women is in fact a response to the demands and limitations of femininity. These demands and limitations may alter over time and across cultures, perhaps even diminish, but wherever they exist, they direct women’s energy towards the body, the self, a terrain over which she has primacy and control. In the current age, it is this notion of control that seems to me to be an integral part of the selfie’s appeal to women. For so long the object of the gaze or invisibilized by it, without the means to represent themselves publicly on their own terms or to preserve their reflection, digital technologies allow women the means to represent themselves as they wish to be seen.

Note No. 6.

To be culturally intelligible as ‘female’ requires interpreting and embodying visual signs. It means wrestling with what de Beauvoir termed the eternal feminine, the mythology of femininity which women are expected to absorb and emanate as effortlessly as if it was their own flesh. The punishment for failing to do so is well documented. Witches. Crones. Spinsters. The ugly bitch. Today some feminists themselves are at pains to point out that they are not – God forbid – the hairy, bad-tempered, femininity-annihilating variety. It is not surprising then that many of the selfies we see in circulation conform, at least at a surface glance, to norms of femininity. Rather than viewing them as a missed opportunity to flout convention, it is perhaps more productive to consider how this apparent conformity speaks to the power and complicated pleasures of women’s relationship to images of the feminine, including images of themselves.

Note No. 8.

The selfie is a site where women look, at themselves, each other, at the world. This may not seem remarkable if you regard looking as an objective activity but as Linda Williams (2002: 61) notes in relation to classic Hollywood cinema, what the female spectator and the female protagonist have in common is their inability to look as men can. This handy arrangement ensures, as Williams writes, that there is ‘no danger that she will return that look and in so doing express desires of her own.’ Without the ability to look, and to have that look acknowledged, expressed, represented, women in culture can never be subjects, only objects. Without overstating the liberatory potential of digital technologies, it is possible to propose that, in the context of the everyday, selfie practices offer a chink in the armour of male gaze dominance, a crack where the light of the female gaze seeps through. If the selfie holds a particular fascination for women, it only takes the briefest glance at the trajectory of Western history to begin to understand why this might be the case. Despite advances towards liberation and a more inclusive culture, visual representation remains, as Griselda Pollock (1988:13) puts it, a site of privilege. It is this privilege that the female gaze disrupts. This disruption – real or imagined – accounts, at least in part, for the withering ire that frequently greets women’s engagement with selfie culture. Just as Rokeby safely directed Venus’s gaze into her mirror, a woman’s look remains a force that must be contained. For if she looks, as Virginia Woolf (2002 [1929]) observed, she ceases to be the passive mirror in which men see their greatness reflected. Under patriarchy, what could be more terrifying than that?

The Rokeby Venus is the only surviving female nude by Velázquez. Nudes were extremely rare in seventeenth-century Spanish art, which was policed actively by members of the Spanish Inquisition. Despite this, nudes by foreign artists were keenly collected by the court circle, and this painting was hung in the houses of Spanish courtiers until 1813, when it was brought to England to hang in Rokeby Park, Yorkshire. In 1906, the painting was purchased by National Art Collections Fund for the National Gallery, London. Although it was attacked and badly damaged in 1914 by the suffragette Mary Richardson, it soon was fully restored and returned to display.

De Beauvoir, Simone (2011 [1949]), The Second Sex, New York: Vintage Books.Pollock, Griselda (1988), Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art, London & New York: Routledge.Williams, Linda (2002), ‘When A Woman Looks’, in Mark Jancovich (ed.), Horror: The Film Reader, London: Routledge, pp.61-67.Woolf, Virginia (2002 [1929]), A Room of One’s Own, London: Penguin Classics.

Are selfies empowering for women?

This is the question Laura Bates asks in this article on "everyday sexism" for the Guardian Life and style pages (Thu 4 Feb 2016). Here is an extract:

A Pew Research Center report in 2014 found that 68% of millennial women had posted a selfie, compared to 42% of millennial men, and only 24% of members of Generation X. And a One Poll survey for the website feelunique.com last year claimed that the average 16-25-year-old woman spends more than five hours a week taking selfies.

If 2015 was the year of the dangerous selfie, 2016 is seeing the medium elevated to new cultural heights. Argentinian-born artist Amalia Ulman used Instagram selfies to create an extended performance project called Excellences & Perfections, excerpts of which are to go on display at Tate Modern as part of its Performing for the Camera exhibition. The project saw Ulman depict a fake life in three stages: the first introduced her as a Los Angeles “it girl”, the second portrayed a period of drug abuse and a stint in rehab, and the third charted her “recovery” through yoga sessions and healthy juice drinks.

Ulman has said that these distinct phases were inspired by stereotypes of how young women present themselves online, but it is the stereotypical responses she received that are perhaps the biggest eye-openers. Art project or not, to her followers, she was a real and vulnerable young woman – yet she was bombarded with what Slate described as “a mess of envy, disdain and enthusiastic schadenfreude”. When she uploaded a post during her “self destructive” stage, one follower accused her of being “#kindawhiney!” and when she shared a picture of herself crying, another wrote: “Cry me a river.”

Finally, when Ulman appeared to be recovering, people accused her of being boring, calling her an idiot and a bitch. “People started hating me,” she says. “Some gallery I was showing with freaked out and was like, ‘You have to stop doing this, because people don’t take you seriously any more.’ Suddenly I was this dumb bitch because I was showing my ass in pictures.”

In many ways, her work highlights exactly the kind of superficial assumptions people make about women based on image alone. “It’s more than a satire,” she said. “I wanted to prove that femininity is a construction, and not something biological or inherent to any woman. Women understood the performance much faster than men. They were like, ‘We get it – and it’s very funny.’ The joke was admitting how much work goes into being a woman and how being a woman is not a natural thing. It’s something you learn.”

"But is posting selfies an empowering and uplifting activity, or does it reinforce the notion that a woman’s value lies solely in her looks?" asks Laura Bates.

She references this body image survey for Today and AOL, saying:

The statistics don’t have a clear answer. A body image survey by Today and AOL found that 65% of teenage girls said seeing their selfies on social media boosted their confidence. However, 55% said social media made them more self-conscious about their appearance and 58% agreed that “seeing pictures of other people living glamorous-looking lives on social media makes me feel bad about myself”.

“Selfie campaigns” arouse similarly mixed responses: the “no makeup selfie” – started to raise money for breast cancer charities – was both praised as brave and uplifting and criticised for suggesting it was scary or daring for women to be pictured without makeup.

The issue is complex, not least because the online reception of the images can have as much of an impact as the intent of the creator. When Welsh teenager Maisie Beech posted a “half makeup selfie” online she thought she was doing something fun and empowering. But after the pictures went viral, strangers commented to say she was sick or ugly and some even threatened physical violence, leaving her shocked at people’s cruelty.

Many teenage girls find themselves subject to sexist pressures when it comes to selfies – both expected to present a beautiful, confident image, and navigating extreme criticism or even abuse if they are perceived as too sexy, “slutty” or posed.

There is a tendency to derisively dismiss selfies as narcissistic, but it’s no coincidence that so many of the young women who have hit the headlines for using them are doing so in response to sexist societal norms or abuse – from damaging, unattainable beauty ideals, to the hacking of women’s private photographs. While female celebrities are accused of being self-obsessed and oversharing, one could equally see their selfie habits as a clever means of taking back control of their own image from the male-dominated media and paparazzi. It’s also worth noting the palpable sneering and contempt for selfies (which most people would hesitate to regard as an art form) may well be influenced by the fact that society views them as a predominantly young, female creation.

But it is encouraging to see the considerable number who are pulling the rug out from under the traditional criticisms of selfies by harnessing the medium to send their own powerful, often feminist messages.

Kim's emojis

"new feminism-themed Kimojis, sparks huge debate online"

There's no point pretending . . .

Baudelaire's inciteful "insight" is that we already know! We already know about art, mysogyny, pornography, patriarchy, and we act upon this knowledge, reactively rather than decisively when offered the "bait" and an invitation to "click", well, then we "click". Distracted from distraction by distraction, the art and purpose of advertising is not to "illuminate" but to obscure, to cover and distract. We respond, and in response generally prefer to create a certain kind of focus, that's a weak sort of consciousness, upon the something, whatever it is, that titillates or arouses. Meanwhile the subliminal effects embedded in the imagery are able to work at full power upon our susceptibilities. There are no boundaries in this sort of territory, just echoes and resonances.

Marshall McLuhan creates an "apposition" to the Baudelaire quote from Les Fleurs du Mal "— Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère!, " through the positioning of another quote, this one from Finnegans Wake by James Joyce:

My consumers, are they not my producers?

Is this true equally for the artist, the celebrity and the "brand"? Both of these quotes point to a reversal where consumer, reader, spectator becomes the producer, as actors in a process of creation as well as interpretation. It is the "reader", sister and/or brother, as consumer and/or producer, that is ultimately responsible for creating the stuff of art, along with the stuff of life and, occasionally, an understanding of the world in which we live, breathe, eat, sleep, make love and die.

No comments:

Post a Comment