"Thousands of workers from across West Java staged a rally in Bandung on Wednesday, demanding the implementation of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement be postponed in Indonesia."

This is a quote from the report in The Jakarta Post from Bandung on January 7 2010.

The protesters expressed fears that once the FTA came into effect it would trigger mass layoffs, as well as Indonesian products’ inability to compete on international markets.“I’m afraid that forcing this [FTA] will lead to millions of workers being laid off because of the relatively higher prices of Indonesian goods compared to those from China,” said Baharudin Simbolon of the Association of Indonesian Labor Union’s West Java chapter, during the rally outside the governor’s office.The protesters urged both the governor and provincial legislature to propose President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono postpone the FTA until the government reduced all unnecessary operational costs that had made it impossible for Indonesian products to compete in ASEAN markets.

“In terms of bank interest rates, for example, they’re up to 16 percent here, while in China they’re only between 4 and 6 percent. This excludes other unnecessary levies that further burden the business world domestically, making it difficult for us to compete,” he said.

However, Simbolon said he understood that the multilateral agreement could not be cancelled just because of the Indonesian government’s rush to sign it without considering or anticipating its negative impacts on the domestic market. For this reason, he said postponement was the best option.

Uye Guntara of the Association of Bandung Leather and Textile Workers, who has seen many workers being dismissed as a result of the global crisis, also said he feared potentially massive layoffs as a result of the implementation of the FTA.

“The global crisis has already impacted the textile industry. The ASEAN-China FTA is feared to make things worse,” Uye said.

Protesters in Tuesday’s rally came from various regions including Bandung, West Bandung, Cimahi, Sumedang, Bogor and Depok, forming a large crowd around the Sate Building complex that houses the governor’s office and the provincial legislature building.

Anticipating traffic congestion from the rally, police decided to temporarily close the street. They also deployed up to 2,000 personnel to secure the rally that was expected to mobilize up to 50,000 workers.

Carrying banners condemning the Cabinet for its failure to address economic problems properly, protesters took it in turns to make speeches on a car stage. Some of their banners read “Say No to Free Trade”, “Budiono Resign”, “Fire Sri Mulyani” and “Run Pro-People Programs”.

“We will enjoy poverty, collectively, if cheap Chinese products are allowed to enter Indonesia without tariffs. The government and neo-lib Cabinet have just taken sides with foreign interests,” Sumarna, a protester, said in his speech.

Separately, the deputy chairman of the Association of Indonesian Businesspeople (APINDO) West Java chapter, Deddy Wijaya, said there up to 40,000 workers would be laid off in just three months following the implementation of the ASEAN-China FTA, with up to 30 percent of the 8,000 members of the association facing bankruptcy.

“The biggest impacts will become visible in the second semester,” he said.

Many, including West Java Manpower Agency chief Mustopa Djamaludin, have expressed support for workers’ demands, and that they would send the central government a special recommendation to temporarily withdraw itself from the ASEAN-China FTA.

Mustopa said so far 40 companies in the province had proposed a postponement of the 2010 regional wage regulation, saying their businesses were not healthy. The same postponement was proposed by 87 companies last year.

“Although the number of companies proposing the postponement is less than it was last year, we still have to anticipate [future developments],” Mustopa said,

In 2011 Anne Booth, SOAS, University of London, contextualised these concerns in a paper: China’s Economic Relations with Indonesia: Threats and Opportunities.

The paper examines the development of China‟s economic ties with South East Asia over the last two decades, culminating in the inauguration of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement in 2010. Particular reference is made to China‟s trade ties with Indonesia. Although two-way trade between China and Indonesia has grown rapidly since 2000, Indonesian exports to China are dominated by primary products, while imports from China are dominated by manufactures. While this pattern might reflect short-term comparative advantage in both economies, it is causing some concern in Indonesia. The paper assesses these concerns, and possible political reactions.

Free trade? Who benefits?

The ASEAN–China Free Trade Area (ACFTA), is a free trade area among the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the People's Republic of China.

A section of this paper focuses on the Indonesian economic and political situation entitled, The Indonesian Growth Slow-down and Recovery: Causes and Consequences.

The following section of this paper is entitled: The China-ASEAN FTA, and looks at concerns across the region as to possible disadvantages that this Free Trade Agreement would lead to in its impact upon particular economic sectors of the ASEAN countries.

The section ends with the following paragraph:

Indonesian fears were expressed in an opinion piece in Indonesia's leading English-language paper, published in October 2010, which pointed out that "most people are of the opinion that Indonesia's agricultural products and manufacturing goods are extremely uncompetitive against China's". It went on to argue that instead of seeing the China-ASEAN free trade agreement as an instrument to strengthen the interdependence of the ASEAN region with China, many Indonesians see it as leading to "cut-throat competition that will have negative impacts on the development of Indonesian economic capabilities in the long term". Others view Chinese policies as essentially neo-colonial;

In its hunger for raw materials, China is in effect seeking to re-impose colonial patterns of trade on Southeast Asia.It is too early to tell if these fears are justified or not, but they appear to reflect widely held beliefs in Indonesian business, media and political circles.

Factory workers in China

The conclusion to this 2011 paper, The Indonesian Growth Slow-down and Recovery: Causes and Consequences, looks at both the regional and global implications of this Free Trade deal. It also raises concerns about how a rising nationalism might expose Indonesians of Chinese origin to becoming the target for future resentment, as had occurred in the tragedy of May 1998. This tragedy is referenced in the Glodok Information Wrap in the article Do the pogroms of the past still haunt the Chinese Indonesians of today?

The official enthusiasm in China for the ACFTA has raised suspicions in several parts of ASEAN, including Indonesia, that the Chinese will use it to their own advantage. On the import side, they will continue to press for access to Southeast Asia's raw materials while continuing to impose barriers to imports from ASEAN of both agricultural and manufactured goods which might threaten their own producers. These suspicions are in turn based on fears about the motivations of Chinese foreign economic policy. Is China treating the major ASEAN governments in the same way that it has dealt with several regimes in Africa, whose governments have granted China access to oil, mineral resources, and even agricultural land, on favourable terms in exchange for loans and other forms of economic assistance? Certainly this has been the case in Myanmar, where Chinese economic support has been, and continues to be, essential for the survival of the regime. Indonesia, along with countries such as Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines, are far from being client states of China, and economic relations should be conducted on the basis of mutual benefit, and respect for WTO procedures.

But at the same time, it is clear that China's growing export power has forced several ASEAN countries to re-evaluate their longer-term comparative advantage. The ASEAN-4 (Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia) all made progress in increasing the share of manufactured exports in total exports over the decades from the 1970s to the 1990s, although exports of oil and gas and other mineral and agricultural products remained important in Indonesia, even after the reforms of the late 1980s led to rapid growth of exports of manufactures. Although it is true that Indonesia after the crisis of 1997/98 has not been as successful as Thailand in benefiting from the growth of trade in parts and components, it has continued to develop land-based export products such as palm oil, while at the same time taking advantage of growing world demand for both gas and other mineral products including coal. In addition, as this paper has argued, exports of garments, footwear and electrical products have increased in recent years, in spite of increased competition from China and other exporters including Pakistan.

But it is undeniable that fears of current Chinese intentions regarding the ACFTA have reinforced long-standing resentments on the part of indigenous Southeast Asians concerning the economic role of their own Chinese minorities. A pessimistic view of the future is that discontent on the part of both industrial and agricultural workers over “unfair” Chinese competition in Indonesia could spill over into violence against the Chinese minority, especially if trading companies owned by Indonesians of Chinese origin are seen to be benefiting from sales of merchandise originating from China. The greater political openness in the post-Soeharto era has encouraged some politicians to embrace economic nationalism in its more extreme form, with strong anti-Chinese undertones. It is quite possible that these elements will exploit resentments concerning the outcomes of the ACFTA. This in turn could lead to tensions within ASEAN, which could slow progress towards an ASEAN single market, which will remain the primary objective of ASEAN foreign economic policy over the next few years. A more optimistic view is that Indonesian producers of a range of primary and manufactured products will benefit from surging Chinese demand, while Indonesian producers and consumers will benefit from cheaper imports of capital equipment and consumer goods. Which view will prevail in coming years is difficult to predict.

The politics and economics of South-south cooperation

A new direction for international co-operation?

This article, to be found on the Poverty matters blog, supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and published in 2011, begins on an optimistic note:

One of the many revolutions taking place in the world of international aid and co-operation is the rebirth of a movement that challenges what is now generally described as the "traditional" aid model. Instead of a vertical donor-recipient approach to aid giving, south-south cooperation (SSC) emphasises horizontality and mutuality.

At a conference in Bogotá last week, sponsored by the Colombian and Indonesian governments, delegates reaffirmed their view that, with developing countries growing fast, SSC has as much to say about the future of international development as western aid.

It is one of the big ideas on the development landscape and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), to its credit, is fully supporting it – despite the challenging critique of OECD donor practices at its heart. While the first draft of the outcome document for the Busan Aid Effectiveness conference hardly mentioned SSC, the latest draft has a whole section on it.

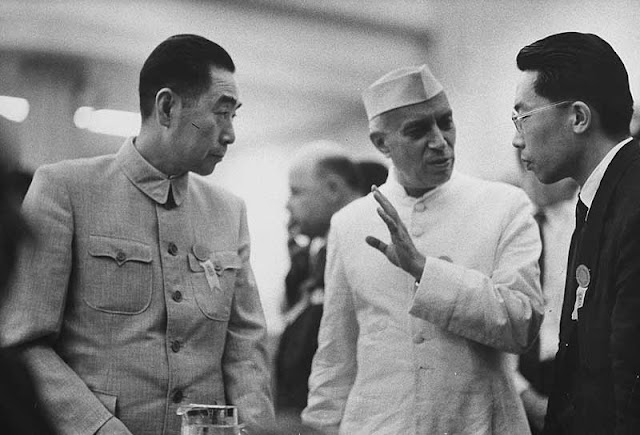

SSC aficionados say it all began at a 1955 conference in Bandung, Indonesia, which set out plans for economic and social co-operation between Asia and Africa. Some 29 countries representing more than half the world's population sent delegates, and condemned "colonialism in all of its manifestations". But SSC has been revitalised recently as the hegemony of the west has faltered, allowing other powers and theories to enter the fray.

SSC is much more than just another aid modality. As well as financing, SSC consists of exchange of experts, technical assistance, goods and services (in kind), information on best practices, and initiatives to increase joint-negotiation capacities.

But its political significance may be as important as its anticipated concrete impacts. At its most radical, SSC challenges a form of development that has served northern interests more than those of the "recipients" of aid. While trying to stay generous in their outlook towards northern donors, who still provide the vast majority of aid, proponents of SSC implicitly challenge the traditional aid approach as self-serving, patronising and lacking in imagination.

The fact of the co-operation of the Indonesian and Colombian governments during this period is an interesting coincidental connection, because for the LODE and Re:LODE project both these countries are along the LODE Zone Line.

The Wikipedia article on South-South cooperation also references the Asian–African Conference that took place in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955, which is discussed in the Cargo of Questions article on the Maribaya Information Wrap page.

The formation of SSC can be traced to the Asian–African Conference that took place in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955 which is also known as the Bandung Conference. The conference has been largely regarded as a milestone for SSC cooperation. Indonesia's president at that time, Sukarno, referred to it as "the first intercontinental conference of coloured peoples in the history of mankind." Despite Sukarno's opening address about the conference, there had been gatherings similar to the Bandung conference in the past. Nevertheless the Bandung Conference was distinctive and facilitated the formation of SSC because it was the first time that the countries in attendance were no longer colonies of distant European powers. President Sukarno also famously remarked at the conference that "Now we are free, sovereign, and independent. We are again masters in our own house. We do not need to go to other continents to confer."

Sukarno was, up until he was removed from the presidency, increasingly convinced that Chinese models, in terms of both economic and political strategic approach, were ones that Indonesia could learn from and apply to local conditions. In the more recent context of South-South cooperation China continues to lead in taking the initiative. For example, according to the Wikipedia article on South-South cooperation, it is China that has met the challenge when it comes to the lack of sufficient capital to start a South–South bank as an alternative to the IMF and the World Bank.

This has changed with the launch of two new 'South–South banks'. At the sixth summit of the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa), in July 2014, the five partners approved the establishment of the New Development Bank (or BRICS Development Bank), with a primary focus on lending for infrastructure projects. It will be based in Shanghai. A Contingency Reserve Agreement (CRA) has been concluded in parallel to provide the BRICS countries with alternatives to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund in times of economic hardship, protect their national economies and strengthen their global position. The Russian Federation is contributing US$18 billion to the CRA, which will be credited by the five partners with a total of over US$100 billion. The CRA is now operational. In 2015 and 2016, work was under way to develop financing mechanisms for innovative projects with the new bank’s resources.

What is new about the New Development Bank?

The second new bank is the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. It has also been set up to finance infrastructure projects. Spearheaded by China, the bank is based in Beijing. By 2016, more than 50 countries had expressed interest in joining, including a number of developed countries: France, Germany, the Republic of Korea, United Kingdom, etc.

The Belt and Road Initiative

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a global development strategy adopted by the Chinese government involving infrastructure development and investments in 152 countries and international organizations in Asia, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. "Belt" refers to the overland routes for road and rail transportation, called "the Silk Road Economic Belt"; whereas "road" refers to the sea routes, or the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

It was known as the One Belt One Road (OBOR) (Chinese: 一带一路) and the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road (Chinese: 丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路) until 2016 when the Chinese government considered the emphasis on the word "one" was prone to misinterpretation.

The Chinese government calls the initiative "a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future". Some observers see it as a push for Chinese dominance in global affairs with a China-centered trading network. The project has a targeted completion date of 2049, which coincides with the 100th anniversary of the People's Republic of China.

The initiative was unveiled by Chinese paramount leader Xi Jinping in September and October 2013 during visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia, and was thereafter promoted by Premier Li Keqiang during state visits to Asia and Europe. The initiative was given intensive coverage by Chinese state media, and by 2016 often being featured in the People's Daily.

Initially, the initiative was termed One Belt One Road Strategy, but officials decided that the term "strategy" would create suspicions so they opted for the more inclusive term "initiative" in its translation.

The "21st Century Maritime Silk Road" (Chinese: 21世纪海上丝绸之路) , or just the Maritime Silk Road, is the sea route 'corridor'. It is a complementary initiative aimed at investing and fostering collaboration in Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Africa, through several contiguous bodies of water: the South China Sea, the South Pacific Ocean, and the wider Indian Ocean area. It was first proposed in October 2013 by Xi Jinping in a speech to the Indonesian Parliament. Like the Silk Road Economic Belt initiative, most countries have joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Update

What is China's Belt and Road Initiative?

In 2016, China Railway International won a bid to build Indonesia's first high-speed rail, the 140 km (87 mi) Jakarta–Bandung High Speed Rail. It will shorten the journey time between Jakarta and Bandung from over three hours to forty minutes The project, initially scheduled for completion in 2019, was delayed by land clearance issues.

President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo (left) inspects a scale model of a high-speed train that will connect Jakarta to the country's fourth-largest city, Bandung, during the groundbreaking ceremony for the construction of its railway in Cikalong Wetan, West Java, on Jan. 21, 2016.

News Desk

The Jakarta Post

Jakarta / Mon, February 19, 2018

State-Owned Enterprises Minister Rini Soemarno has said the construction of the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway project will fail to meet its completion target in 2019 due to problems in land acquisition.

She said in Jakarta on Monday as of now, the land acquisition only reached 54 percent of the 140-kilometer total length of the project, or 55 km.

She added the constructor had prepared the construction on 22 km of acquired land and conducted land clearance on the remaining 33 km.

“The project location was only decided on Oct. 31, 2017. There are still many plots of land, [whose conversion from forest land] should be agreed on by the Environment and Forestry Ministry,” Rini said at the Office of the Coordinating Economic Minister as reported by kontan.co.id.

She said the construction would start this month and was expected to be completed in October 2020.

Land clearance issues? Forest?

Can Indonesia avoid the Chinese debt trap?

Indonesia News Now

August 4, 2019

Indonesia signed 23 collaborative projects in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) scheme at the BRI conference in Beijing on April 26, 2019, which include projects in North Sumatra, North Kalimantan, North Sulawesi, Maluku, and Bali.

These projects consist of the construction of industrial estates and supporting infrastructure, waste processing power projects, and a technology park. However, the question is whether these initiatives can ultimately benefit Indonesia? What risks must be faced and considered by Jakarta?

The Chinese scheme, formerly known as the One Belt One Road, is often seen as controversial. The BRI itself is a global development strategy initiated by China’s Xi Jinping in 2013.

At present, the program has attracted the involvement of more than 20 countries around the world, and has facilitated the construction of several factories, ports, and other commercial facilities in the participating countries.

In Indonesia, many parties have criticised the country’s involvement in the BRI. Some argued that this scheme would give birth to a debt trap.

This has begun to be seen in Africa, where relatively poor African countries receive large Chinese infrastructure investment funds and use these funds for their national infrastructure development projects which are also run by Chinese companies.

For example, Tanzania’s President John Magufuli recently froze the construction of Bagamoyo Port, which was to become one of the largest ports in East Africa, due to a number of exploitative agreements.

Another example is a debt-for-equity swap agreement between China and Sri Lanka, where China was willing to remove Sri Lanka’s debt of $8 billion if the Sri Lankan government agreed to lease the Hambantota Port to China for 99 years.

Indeed, it cannot be ignored that a large part of the Belt and Road Initiative is in China’s political and economic interests. Many of these initiatives have been carried out to put China in a favorable position. But this does not mean that there are no benefits that countries like Indonesia can take from the BRI scheme, as long as they take steps to protect their national interests.

Indonesia’s homework to reap benefits from the BRI

Many Chinese infrastructure projects in Africa, for example, are very beneficial for recipient countries, the whole continent, and even global trade interests. These projects include railroad infrastructure projects, roads, ports and even a 2,600 megawatts of electricity generation projects in Nigeria as well as $3 billion-dollar telecommunications projects in Ethiopia, Sudan, and Ghana.

The Indonesian government has tried to seek optimal benefits, while at the same time minimising risks by directing Chinese investments as B2B (business to business) activities. In this case, the government plays a role more as a facilitator of investment and development. A number of countries in Africa are not as thorough as Indonesia, where they give governments guarantees for BRI projects.

There are several steps that need to be taken so that Indonesia is able to absorb the benefits of BRI without falling into the Chinese debt trap.

First, Chinese investments must be directed to industries that have high added value, both from economic, technological, and other perspectives and not something that the country can do on its own domestically.

Secondly, there must be technology transfer from China to Indonesia, so that the latter can further advance its industry in the future and its people not only act as consumers.

Third, all of these industries must be environmentally sustainable in order for natural resources, the environment, and surrounding communities to be protected.

Fourth, the BRI projects must use Indonesian workers. This is to provide opportunities and work experience for Indonesian workers. Lastly, these projects must be realised according to international level best practices.

Besides that, it must be realised that the current world trend is changing from a confrontation scheme to a collaborative pattern. Rejection of BRI will not likely to be a realistic step. Collaboration with China, as long as it is managed by considering several aspects mentioned above, is a golden opportunity that Indonesia must continue to use for its own good.

No comments:

Post a Comment