"A lone a last a loved a long the riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs."

This GIF of reeds moving in the flow of the stream takes its inspiration from the cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky. This was probably the case with the LODE sequence below, just as the LODE Super8 documentation process was inspired by this place Harristown, with a river running through it, but also through, and by, the very way realities are revealed through an artistic process. Nearby, and along the LODE Zone Line, on the pathway leading to to the Wicklow mountains, a midden heap of the detritus of everyday life despoils the scene with another type of truth, a truth that has an equal value in the generation of questions, questions we can share and use together.

Rivers being rubbished! Is this where we are now?

The World's Dirtiest River: Today we take you to the world’s most polluted river. 35 million people rely on the Citarum river on the island of Java, Indonesia, but it has become a toxic river of waste. Seyi Rhodes went to the island for this Unreported World classic in April 2014.

Update Jan 25, 2020

This DW Documentary re-visits the continuing environmental catastrophe being wreaked upon Java's Citarum river, the world’s most polluted river. One of the main polluters is the fashion industry: 500 textile factories throw their wastewater directly into the river.

"The filmmakers teamed up with international scientists to investigate the causes and consequences of this pollution. With the help of concerned citizens, the ‘Green Warriors’ team analyzed water samples, rice, children’s hair, etc. and discovered that toxic chemicals are endangering the lives of the 14 million Indonesians who use the Citarum water. What was once considered paradise is now a brown sludge of human waste and dangerous substances like nonylphenol, antimony and tributylphosphate. These findings prompted the Indonesian government to change its wastewater regulations. Recently, President Joko Widodo announced a new plan to clean up the Citarum. The fashion brands questioned in this documentary promised to better monitor their Indonesian suppliers."

The Citarum river is referenced in the LODE & Re:LODE Information Wrap for Maribaya, Java, in the article: Globalisation - industry versus the environment.

James Joyce plays with words, with sounds of words and the meaning of words that comes from how both he and we use them. Riverpool is a word he invents for the Anna Livia Plurabelle chapter, Chapter 8, and it is one for us in the LODE & Re:LODE project. As Peter Quadrino says:

In Joyce’s numerology the number 8 is associated with the female, the feminine life-renewing energy, perhaps because 8 is the symbol of infinity ∞ upright. In Ulysses, the 18th chapter is dedicated to Molly Bloom's final soliloquy consisting of 8 long sentences, and her birthday is on September 8th (also the birthday of the Virgin Mary). The centrality of the female in his final work is hinted at right from the opening word of Finnegans Wake, “riverrun” which contains 8 letters.

Here is some more "Super8"

Tarkovsky - an inspiration

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris Shot by Shot: A 22-Minute Breakdown of the Director’s Filmmaking can be found at OPEN CULTURE.

Peter Quadrino, explores the Anna Livia Plurabelle Chapter 8, in the reflected light of a Book Review (Part 4 of 4): Joyce's Book of the Dark by John Bishop, posted on November 1, 2014. Quadrino writes:

The chapter opens with the text forming a triangular shape, the delta symbol ∆ of ALP:

tell me all about

Anna Livia! I want to hear all

about Anna Livia. Well, you know Anna Livia? Yes, of course,

we all know Anna Livia. Tell me all. Tell me now.

The ALP chapter consists entirely of a dialogue between two washerwomen scrubbing clothes on opposites sides of a river while chattering and gossiping to each other about ALP and her husband.

All throughout the chapter, the inquisitive washerwoman (later referred to as “Queer Mrs Quickenough” FW p. 620) excitedly begs her opposite (“odd Miss Doddpebble” FW p. 620) to divulge more about Anna Livia: “Onon! Onon! tell me more. Tell me every tiny teign. I want to know every single ingul” (FW p. 201).

As the chapter comes to a close, night begins to fall, the river widens and rushes more loudly, and the two women can no longer hear each other over the “hitherandthithering waters of. Night!” (FW p. 216).

A beautiful audio recording from 1929 captures Joyce reciting the closing pages of ALP with a playful and theatrical brogue, giving us our one single glimpse at how he intended his enigmatic work to sound. It’s noticeably mellifluous and musical, with Joyce rolling his r's and lilting the vernacular between the two chattering washerwomen.

John Bishop acknowledges that this flowing sonority is the most frequently praised feature of the chapter, but as with the rest of the Wake though, there is so much more to this poetic prose than its "sounddance" (FW p. 378). Initiating the need to explore deeper into the sediments of ALP, Bishop admits:

“Not many readers, however, are likely to struggle through very many pages of prose so torturous as the Wake’s simply because, though they may not mean anything, they sound nice.”It is this often overlooked meaning that Bishop endeavours to elucidate.

For the ultimate crescendo of his unique and fascinating analysis of the Wake, Bishop devotes the final chapter of his Book of the Dark study to an investigative plunge into the “riverpool” (FW p. 17) of Anna Livia. With Joyce putting so much emphasis and hard work into his showpiece chapter, Bishop surmises, “we might make the chapter something of a test case of the book as a whole.”

Similarly, while there are so many great insights throughout Bishop's Book of the Dark, its final chapter is so rich, enlightening, original and compelling that it could in fact stand as a “test case” for Bishop’s book as a whole. So, to conclude this lengthy summary of Bishop’s delightful and dense book, we shall take a close look into this last chapter, which he entitled "A Riverbabble Primer."

Emphatically putting the final flourishing touches on his fascinating and well-argued thesis that Finnegans Wake represents a rendering of the sleeping state of one man, Bishop takes a microscope to the vivacious streams of the ALP chapter to confirm his theory. He finds ALP’s massive network of rivers is undulating with the sound and pace of a pulse. In short, Bishop argues that the riverwoman Anna Livia Plurabelle represents the watery bloodflow heard pumping inside the sleeper’s body throughout the night.

This accounts for the overall back-and-forth dialogue structure as well as the recurrent rhythm of twos found “ufer and ufer” (FW p.214) again, echoing the binary sounds heard in “the pulse of our slumber” (FW p. 428). The sleeping mind absorbs and amplifies these sounds, unconsciously creating the dream association of flowing rivers until the sleeper becomes immersed in a “watery world” (FW p. 452).

Bishop extends this thread of logic further until we envision the sleeper lying in "foetal sleep" (FW p. 563) with the sounds of pulsing bloodflow triggering reminiscence of and regression to the prenatal bliss of "whome sweetwhome" (FW p. 138) when he was united with the body of his mother or “himother” (FW p. 187). Two hearts beating as one, “uniter of U.M.I. hearts…in that united I.R.U. stade” (FW p. 446).

Of course this is a very radical and unique idea, unlike any interpretation of ALP any Wake scholar has put forth before. It's also fun to ponder and Bishop, a scholar with about as much knowledge about Finnegans Wake as anyone else in the world (he’s been reading it for over 40 years and wrote the introduction to the Penguin edition), presents a most compelling case with his often spellbinding wizardry of exegesis.

Beginning his inquiry into ALP, Bishop examines the chapter’s final paragraph, worth quoting here in full:

Can't hear with the waters of. The chittering waters of. Flittering bats, fieldmice bawk talk. Ho! Are you not gone ahome? What Thom Malone? Can't hear with bawk of bats, all thim liffeying waters of. Ho, talk save us! My foos won't moos. I feel as old as yonder elm. A tale told of Shaun or Shem? All Livia's daughtersons. Dark hawks hear us. Night! Night! My ho head halls. I feel as heavy as yonder stone. Tell me of John or Shaun? Who were Shem and Shaun the living sons or daughters of? Night now! Tell me, tell me, tell me, elm! Night night! Telmetale of stem or stone. Beside the rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of. Night! (FW p. 215-16)Despite his apparent absence on the surface, Bishop detects the presence of the sleeping and absent-minded man at the center of it all, HCE. His body knocked out, lying “Dead to the World” (FW p. 105), the sleeping figure’s “foos won’t moos” and his “ho head halls” because from head-to-toe he is unconscious and sunken by gravity into his bed, so that “I feel as old as yonder elm” and “I feel as heavy as yonder stone.”

As always with HCE though, “Earwicker, that patternmind, that paradigmatic ear” (FW p. 70) the ever-vigilant ears remain awake. Throughout the entire ALP chapter, those ears have ostensibly been overhearing a dialogue between two invisible washerwomen. As the chapter closes those ears are, according to Bishop, deciding whether to turn their attention outward to the sounds of “flittering bats, fieldmice” and whatever else creeps around at night, or to turn inward back to the sounds of the body where (in Bishop’s words) “a deafening rush of waters everywhere audible at the background of the world threatens to drown all hearing out.”

The fluid, splashy cadence of the washerwomen’s dialogue echoes these “chittering waters of… rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of. Night!” and Bishop leads us to believe these waters are actually the surging pulse of watery bloodstream in the sleeper’s ears. We find a hint in the conflation of “them” and “him” in the word “thim” from this paragraph: “all thim liffeying waters of.” These waters, streaming through an unfathomably vast network of river names, are one with the sleeper, HCE.

Moreover, in a revealing bit of detective work Bishop looks back at a passage from Ulysses, where the incisive scientific-thinker Leopold Bloom observes two barmaids holding a seashell to each other’s ears: “hearing the plash of waves, loudly, a silent roar… The sea they think it is. Singing. A roar. The blood is it. Souse in the ear sometimes. Well, it’s a sea. Corpuscle islands.

Bloom’s perspective helps to uncover Joyce’s and here we imagine the sea of blood in the human body that can be heard as a “souse in the ear sometimes” (souse meaning “the sound of water surging against something” according to the OED). And indeed, the sleeper in the Wake whose ears remain awake is surrounded by the ever-present sound of the “pulse of our slumber” (FW p. 428) and “the heartbeats of sleep” (FW p. 403). For while our hero seems lifeless in repose, “his heart’s adrone, his bluidstreams acrawl” (FW p. 74). Therefore, the “rivering waters of… Night!” are the sounds of deepest sleep since, as the Wake elsewhere attests, when HCE has completely succumbed to unconsciousness “to pause in peace… he would seize no sound from cache or cave beyond the flow of wand was gypsing water, telling him now, telling him all…” (FW p. 586 [Danish vand means “water”]).

To strengthen the viability of his theory, Bishop points out the prominence of this idea in studies on dreams and sleep. Havelock Ellis, for instance, wrote: “An increased flow of blood through the ear can furnish the faint rudimentary noises which, in sleep, may constitute the nucleus around which hallucinations crystallize.” Similarly, Freud wrote in dreams “all the current bodily sensations assume gigantic proportions” while in the eleventh Encyclopedia Britannica, the same edition Joyce plundered when writing the Wake, it states “the ear may supply material for dreams, when the circulation of the blood suggests rushing waters or similar ideas.”

With this foundational idea established, Bishop now begins plucking quotes from the pages of “Anna Livia Plurabelle” and notates the dozens and dozens of references to “nothing more than arteries and vessels of moving water (rivers).” You’ll also notice a main recurring theme in the chapter’s dialogue is hearing:

“Listen now. Are you listening? Tarn your ore ouse! Essonne inne!” [Turn your ear loose! Listen in!] (FW p. 201)Embedded all throughout the text of ALP are the names of rivers and these lines, just a small sampling of what Bishop shares, are flooded not only with river names like Essonne, Moselle, and Mezha, you can also find the words “moat”, “deluge”, “ufer” (German Ufer for “riverbank”), “pond”, “oceans” and others here.

“Well, I never heard the like of that! Tell me moher. Tell me moatst” (FW p. 198)

“Make my hear it gurgle gurgle in the dusky dirgle dargle!... But you must sit still. Will you hold your peace and listen well” (FW p. 206)

“Oceans of Gaud, I mosel hear that!” (FW p. 207)

“Mezha, didn’t you hear it a deluge of times, ufer and ufer, respund to spond?” (FW p. 214)

On the surface, the dialogue features one washerwoman begging to hear stories about Anna Livia from the other one. Viewed through the lens of Bishop’s theory, the lines take on a whole new life and “bring to mind the…out of sight” (FW p. 200), the sounds of streaming water, the liveliness heard in the deepest night. As told by Bishop:

Particled together of terms largely signifying arteries of moving water---rivers---these lines orient the chapter at the interior of Earwicker’s ear, which “overhears,” in the absence of all other sound, the vitality of its own bloodstream.And then, further on, regarding the hundreds of river names:

Far from obscuring the chapter… [Joyce] was highlighting essential “hydeaspects” (FW p. 208) of the chapter; what readers have largely seen as a “mere device” motivated by an eccentric obsession was in fact an elucidative necessity crucial to the formation of a text representative of waters washing through the ear.

. . . waters washing through the ear

Madonna by Salvador Dali 1958

Salvador Dali was exceptionally gifted in the visual interplay, or "washing through" of ear, eye and nose, as in this "cool" low definition/high definition apparition glimpsed in this detail of his Madonna of 1958.

Dali's take on sensory interplay cast in classical sculptural form is weirdly effective too.

The "effect" (and the affect) of this imagery is explainable via reference to the phenomenon in human communication called "catechresis", that is the use of a deliberate discrepancy to make an unsettling but complex point. Perhaps it's worth mentioning here that "making a point" originates in the spontaneous interaction between performer and audience in the eighteenth century state-licensed theatres of London and Paris. The repertoires were well known and the anticipation of audiences at certain favourite moments in a play meant that when actors arrived at such a "point" they were expected to come down to stage front and centre and deliver their lines full face to the crowd. If the actor appeared to have done well the audience would call for a repeat. These encores could go on seven or eight times.

Ear and eye

The unsettling imagery Dali instigates in the swapping of location of human sense organs was used later in the graphic design of The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects, a book co-created by the creator of media analysis Marshall McLuhan and graphic designer Quentin Fiore, with coordination by Jerome Agel, and first published by Bantam books in 1967.

McLuhan's understanding and appreciation of James Joyce's achievement in Finnegans Wake is clearly evident in the double page spread shown below (pp.120, 121), especially focussing on the idea of "sacral or auditory man", exemplified in Joyce's quoted text.The substitution of an ear for an eye (aye) was presented, performatively rather than illustratively, in the photomontage created by photographer Peter Moore for the book design and including the apposition of images with text that would powerfully reinforce the flow of ideas being explored. As McLuhan has it on page 120:

Listening to the simultaneous messages of Dublin, James Joyce released the greatest flood of oral linguistic music that was ever manipulated into art.

As well as this image many of the other photos in The Medium is the Massage were created by Peter Moore, who was closely connected with the Fluxus (as in "flowing") movement, photographing Fluxus activities, happenings, the Judson Dance Theater, multimedia events and other innovative performances from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Riverpool

As Peter Quadrino notes in the introduction to the book review quoted above:

The eighth chapter of Finnegans Wake is perhaps its most famous section. Known for containing the names of over a thousand of the world’s rivers embedded in its prose. Joyce considered the Anna Livia Plurabelle (ALP) chapter to be the showpiece for his entire book. It was his pride and joy, the chapter upon which he was “prepared to stake everything." While the public and his own supporters were questioning the merit (and sanity) of the early published fragments from his Work in Progress, Joyce declared in a letter to his patron “either [ALP] is something, or I am an imbecile in my judgment of language.” Fellow Irishman James Stephens agreed, declaring it to be “the greatest prose ever written by a man.”Joyce went through seventeen different revisions of the chapter during the Wake’s creation, constantly weaving new river names and foreign words into its pun-laden network, while exhausting himself into a “nervous collapse,” as he told Ezra Pound, from the thousands of hours he worked on it.

James W. Cerny writing for the James Joyce Quarterly (Vol. 9, No. 2, Finnegans Wake Issue (Winter, 1972), pp. 218-224 Published By: University of Tulsa) says there are many stories about how Joyce came by so many names of rivers, but it is likely that he would have also pored over the pages of his 1911 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica to contribute to the gathering of such an inventory.

Wikisource reproduces some of the pages from this 1911 publication containing geographical information on river systems and accompanied by maps. An example of this relates to India, then administered by the British Raj as the jewel in the crown of the British Empire:

River systems.

The vast level tract which thus covers northern India is watered by three distinct river systems. One of these systems takes its rise in the hollow trough beyond the Himalayas, and issues through their western ranges upon the Punjab as the Sutlej and Indus. The second of the three river systems also takes its rise beyond the double wall of the Himalayas, not very far from the sources of the Indus and the Sutlej. It turns, however, almost due east instead of west, enters India at the eastern extremity of the Himalayas, and becomes the Brahmaputra of Eastern Bengal and Assam. These rivers collect the drainage of the northern slopes of the Himalayas, and convey it, by long and tortuous although opposite routes, into India. Indeed, the special feature of the Himalayas is that they send down the rainfall from their northern as well as from their southern slopes to the Indian plains. The third river system of northern India receives the drainage of their southern slopes, and eventually unites into the mighty stream of the Ganges. In this way the rainfall, alike from the northern and southern slopes of the Himalayas, pours down into the river plains of Bengal.

Northern table-land

The third division of India comprises the three-sided table-land which covers the southern half or more strictly peninsular portion of India. This tract, known in ancient times as the Deccan (Dakshin), literally “the right hand or south,” comprises the Central Provinces and Berar, the presidencies Northern table-land.of Madras and Bombay, and the territories of Hyderabad, Mysore and other feudatory states. It had in 1901 an aggregate population of about 100 millions.The northern side rests on confused ranges, running with a general direction of east to west, and known in the aggregate as the Vindhya mountains. The Vindhyas, however, are made up of several distinct hill systems. Two sacred peaks guard the flanks in the extreme east and west, with a succession of ranges stretching 800 m. between. At the western extremity, Mount Abu, famous for its exquisite Jain temples, rises, as a solitary outpost of the Aravalli hills 5650 ft. above the Rajputana plain, like an island out of the sea. On the extreme east, Mount Parasnath—like Mount Abu on the extreme west, sacred to Jain rites—rises to 4400 ft. above the level of the Gangetic plains. The various ranges of the Vindhyas, from 1500 to over 4000 ft. high, form, as it were, the northern wall and buttresses which support the central table-land. Though now pierced by road and railway, they stood in former times as a barrier of mountain and jungle between northern and southern India, and formed one of the main obstructions to welding the whole into an empire. They consist of vast masses of forests, ridges and peaks, broken by cultivated valleys and broad high-lying plains.GhatsThe other two sides of the elevated southern triangle are known as the Eastern and Western Ghats. These start southwards from the eastern and western extremities of the Vindhya system, and run along the eastern and western coasts of India. The Eastern Ghats stretch in fragmentary spurs and ranges down the Madras presidency, here and there receding inland and leaving broad level tracts between their base and the coast. The Western Ghats form the great sea-wall of the Bombay presidency, with only a narrow strip between them and the shore. In many parts they rise in magnificent precipices and headlands out of the ocean, and truly look like colossal “passes or landing-stairs” (gháts) from the sea. The Eastern Ghats have an average elevation of 1500 ft. The Western Ghats ascend more abruptly from the sea to an average height of about 3000 ft. with peaks up to 4700, along the Bombay coast, rising to 7000 and even 8760 in the upheaved angle which they unite to form with the Eastern Ghats, towards their southern extremity.The inner triangular plateau thus enclosed lies from 1000 to 3000 ft. above the level of the sea. But it is dotted with peaks and seamed with ranges exceeding 4000 ft. in height. Its best known hills are the Nilgiris, with the summer capital of Madras, Ootacamund, 7000 ft. above the sea. The highest point is Dodabetta Peak (8760 ft.), at the upheaved southern angle.Eastern GhatsOn the eastern side of India, the Ghats form a series of spurs and buttresses for the elevated inner plateau, rather than a continuous mountain wall. They are traversed by a number of broad and easy passages from the Madras coast. Through these openings the rainfall of the southern half of the inner plateau reaches the sea. The drainage from the northern or Vindhyan edge of the three-sided table-land falls into the Ganges. The Nerbudda and Tapti carry the rainfall of the southern slopes of the Vindhyas and of the Satpura hills, in almost parallel lines, into the Gulf of Cambay. But from Surat, in 21° 9′, to Cape Comorin, in 8° 4′, no large river succeeds in reaching the western coast from the interior table-land. The Western Ghats form, in fact, a lofty unbroken barrier between the waters of the central plateau and the Indian Ocean. The drainage has therefore to make its way across India to the eastwards, now turning sharply round projecting ranges, now tumbling down ravines, or rushing along the valleys, until the rain which the Bombay sea-breeze has dropped upon the Western Ghats finally falls into the Bay of Bengal. In this way the three great rivers of the Madras Presidency, viz., the Godavari, the Kistna and the Cauvery, rise in the mountains overhanging the western coast, and traverse the whole breadth of the central table-land before they reach the sea on the eastern shores of India.Of the three regions of India thus briefly surveyed, the first, or the Himalayas, lies for the most part beyond the British frontier, but a knowledge of it supplies the key to the ethnology and history of India. The second region, or the great river plains in the north, formed the theatre of the ancient race-movements which shaped the civilization and the political destinies of the whole Indian peninsula. The third region, or the triangular table-land in the south, has a character quite distinct from either of the other two divisions, and a population which is now working out a separate development of its own. Broadly speaking, the Himalayas are peopled by Mongoloid tribes; the great river plains of Hindustan are still the home of the Aryan race; the triangular table-land has formed an arena for a long struggle between that gifted race from the north and what is known as the Dravidian stock in the south.

Maps of India, Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911

Nowadays there is a list of the rivers of India on Wikipedia, and another Wikipedia list of rivers of Pakistan, separate lists that are politically defined rather than relating geographically to the regions topography. There are also lists of legendary and mythological rivers too, and found on Wikipedia!

The Styx, a legendary river and the Weltlandschaft (world landscape) in art?

Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx, Joachim Patinir, c. 1515–1524, Prado

In Greek mythology, the river Styx (Ancient Greek: Στύξ [stýks], literally "shuddering") is a river that forms the boundary between Earth (Gaia) and the Underworld. The rivers Acheron, Cocytus, Lethe, Phlegethon, and Styx all converge at the centre of the underworld on a great marsh, which sometimes is also called the Styx. Styx is also known as the goddess of the river, the source of its miraculous powers.

This landscape painting depicting Charon Crossing the Styx is an oil on wood painting by the Flemish Northern Renaissance artist Joachim Patinir and fits into Northern European Renaissance and early Mannerist trends of art. The 16th century witnessed a new era for painting in Germany and the Netherlands that combined influences from local traditions and foreign influences. Many artists, including Patinir, travelled to Italy to study and these travels provided new ideas, particularly concerning representations of the natural world.

The painting depicts the classical subject related by Virgil in his Aeneid (book 6, line 369) and by Dante in the Inferno (canto 3, line 78) in the centre of the picture. Consequently this subject is placed within the Christian traditions of the Last Judgment and the Ars moriendi. The larger figure in the boat is Charon, who transports the souls of the dead to the gates of Hades. The passenger in the boat, too minute to distinguish his expressions, is a human soul deciding between Heaven, to his right (the viewer's left), or Hell, to his left. The river Styx divides the painting down the centre. It is one of the four rivers of the underworld that passes through the deepest part of hell. On the painting's left side is the fountain of Paradise, the spring from which the river Lethe flows through Heaven.On the right side of the composition is Patinir's vision of Hell, drawing largely on the influence of Hieronymous Bosch. He adapts a description of Hades, in which, according to the Greek writer Pausanias, one of the gates was located in an inlet. In front of the gates is Cerberus, a three-headed dog, who guards the entrance of the gate and frightens all the potential souls who enter into Hades. The soul in the boat ultimately chooses his destiny by looking toward Hell and ignoring the angel on the river-bank in Paradise that beckons him to the more difficult path to Heaven.This type of composition was given a name, the German term Weltlandschaft, originally first used by Eberhard Freiherr von Bodenhausen in 1905 with reference to Gerard David, and then in 1918 applied to Patinir's work by Ludwig von Baldass, defined as the depiction of "all that which seemed beautiful to the eye; the sea and the earth, mountains and plains, forests and fields, the castle and the hut". Typically this term was then applied to imaginary panoramic landscapes, seen from an elevated viewpoint that included mountains and lowlands, water, and buildings. The subjects of these paintings usually involve a Biblical or historical narrative, although the figures comprising narrative elements are tyically dwarfed by their surroundings.

River of the Arrow

In the novel Kim by Rudyard Kipling, he has a Tibetan Lama in search of "the river of the arrow" a legendary river formed, and springing from the ground where the Buddha's arrow had fallen whilst participating in an archery contest. Kim befriends the Lama and joins him in this quest along with other adventures, including espionage, in the geopolitical context of what Kipling names the "Great Game". Kim is an "outsider", straddling the small world of the narrow political interests of the colonial administration and the larger and wider world he sees from his vantage point travelling along the Grand Trunk Road. The story begins with Kim, an orphan boy of thirteen who lives with a half-caste opium smoking woman in the city of Lahore (now in Pakistan). His father was an Irish sergeant in the British Indian Army and his mother was an Indian nursemaid — both dead. He speaks Hindustani and plays among the Hindu and Muslim boys of Lahore, and in some respects, these overlap with Rudyard Kipling's own early life. Born in Bombay (Mumbai) to a British couple (they had just moved to India) in 1865, Kipling lived the first six years of his life in Bombay. He heard Indian folk tales and songs from his "Hindu bearer" (who would then send him to his parents, with the caution, "Speak English now to Papa and Mamma," as Kipling later wrote in his autobiography, Something of Myself).

Rivers, geographical and political boundaries and LODE

The main reason for the creation of one the LODE cargo/artworks by the River Liffey was that Harristown was a place on the LODE Zone Line that was on the older Norman colonial boundary of a territory and hinterland centred on the port of Dublin and its river, the Liffey, and known as The Pale.

Rivers, coasts, mountains and marsh form natural boundaries but the territorial boundaries of 1911 are reflective of the colonial administration of what was referred to during the British Empire as the Indian subcontinent as a sub-continent. Nowadays the usage of the term South Asia is becoming more widespread since it clearly distinguishes the region from East Asia.

While South Asia, a more accurate term that reflects the region's contemporary political demarcations, is replacing the Indian subcontinent, a term closely linked to the region's colonial heritage, as a cover term, the latter is still widely used in typological studies. What stands out in these maps of 1911, especially in the map of northern India, are the old boundaries of India before the creation of Pakistan and the partition of India in 1947 along religious, political and cultural fault lines.

The map of 1909 represents the territories and prevailing religions of the British Raj (1901), which became in 1947 the basis for the partition. Below this map speculating on a possible division of India was published in the British newspaper the Daily Herald, 4th June 1947.

The partition involved the division of two provinces, Bengal and Punjab, based on district-wide non-Muslim or Muslim majorities. The partition also saw the division of the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Royal Indian Air Force, the Indian Civil Service, the railways, and the central treasury. The partition was outlined in the Indian Independence Act 1947 and resulted in the dissolution of the British Raj, i.e., Crown rule in India. The two self-governing independent Dominions of India and Pakistan legally came into existence at midnight on 14–15 August 1947.The partition displaced between 10 and 20 million people along religious lines, creating overwhelming calamity in the newly-constituted dominions. It is estimated that around 200,000–2 million people died during migration. It is often described as the largest mass human migration and one of the largest refugee crises in history. There was large-scale violence, with estimates of the loss of life accompanying or preceding the partition disputed and varying between several hundred thousand and two million. The violent nature of the partition created an atmosphere of hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan that affects their relationship to this day.

The boundaries of the new nations of India and Pakistan had no obvious geographical or topographical features. And rivers do not contribute to the nw frontiers. The name of the geopolitical, cultural, and historical region the Punjab, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of eastern Pakistan and northwestern India means “five rivers.” So, the region is named for the great rivers that branch through the landscape, creating an ancient cradle of civilization and a modern agricultural breadbasket.

This ancient land was divided between Pakistan and India in the partition of India. As territories, determined politically and bureaucratically, and reflecting the divide and rule policy of the British colonial administration, they divide the lands of British ruled India. India is now ruled by the BJP party, a right wing political project that sows nationalist, racist and religious inspired hatred and division in society in order to maintain its grip on power.

Update: The 2022 floods in Pakistan

The NASA Earth Observatory has reported on the devastating floods in Pakistan caused since mid-June 2022, by extreme monsoon rains that have led to the country’s worst flooding in a decade.

Since mid-June 2022, Pakistan has been drenched by extreme monsoon rains that have led to the country’s worst flooding in a decade. According to Pakistan’s National Disaster Management Authority, the floods have affected more than 33 million people and destroyed or damaged more than 1 million houses. At least 1,100 people were killed by floodwaters that inundated tens of thousands of square kilometres of the country.

The image above, acquired by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-20 satellite on August 31, 2022, shows the extent of flooding in the region. The image uses a combination of near-infrared and visible light to make it easier to see where rivers are out of their banks and spread across floodplains.

The immense volume of rain and meltwater inundated the dams, reservoirs, canals, and channels of the country’s large and highly developed irrigation system. On August 31, the Indus River System Authority authorised some releases from dams because the water flowing in threatened to exceed the capacity of several reservoirs.

The worst flooding occurred along the Indus River in the provinces of Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan, and Sindh. The provinces of Balochistan and Sindh have so far this year received five to six times their 30-year average rainfall. Most of that arrived in summer monsoon rains.

Across the country, about 150 bridges and 3,500 kilometers (2,200 miles) of roads have been destroyed, according to ReliefWeb. More than 700,000 livestock and 2 million acres of crops and orchards have also been lost.

The detailed false colour images of the impact of rainfall and meltwater is revealed in a comparison of the state of things in the area shown on the map above of Pakistan and India's river system in the Punjab on 4 August 2022 and then later on 28 August 2022 respectively. The images are sourced from Landsat 8 and Landsat 9 satellites. The images combine shortwave infrared, near infrared, and red light (bands 6-5-4) to better distinguish flood waters (deep blue) beyond their natural channels.

4 August 2022

28 August 2022

Climate change, colonial exploitation, extreme weather events and the demand for REPARATION

For the LODE project the material connection of rivers, river systems, geography, culture and history merge into an attempt to create a contemporary form of a Weltlandschaft, a . . .

. . . World Landscape!

Bengal and a world landscape

This spectacular wall sized map produced in 1776 by James Rennell covers those parts of India known as Bengal and Bihar. The map follows the course of the Ganges River from Varanasi (Benares) eastward to the Ganges Delta and the Bay of Bengal. It includes the ancient cities of Varanasi (Benares), Dacca (Dahka, Bengladesh), and Patna among many other important Indian cities.

The area mapped out is bounded in the north by the Himalaya Mountains and the border with Bhutan. This is one of the first accurate maps of the interior of India. Laid out from primary surveys done by James Rennell, the first modern cartographer to map the interior of India. There are notes on cities, markets, battlefields, fortresses, roads, rivers, and offers political commentary, and features some geographical references.

The elaborate title in the lower left quadrant indicates the powerful commercial and colonial interests behind such a project, as does the upper right quadrant that features a dedication and letter of thanks written by Andrew Dury, the publisher, to the board of the East India Company. Bengal is riverine region. The James Rennell map of 1776 charts the many rivers and tributaries of the the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta.

Today a satellite image of the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta shows this complex riverine geography in its true colours, and the river delta in the Bengal region of South Asia, including Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal. It is the world's largest river delta as it empties into the Bay of Bengal with the combined waters of several river systems, mainly those of the Brahmaputra river and the Ganges river. It is also one of the most fertile regions in the world, thus earning the nickname the Green Delta. The delta stretches from the Hooghly River east as far as the Meghna River.

The riverine geography of Bengal contributed to the enormous wealth generating capacity of the region over the centuries. When the Mughal Empire conquered Bengal in the 16th century it was the wealthiest state in the subcontinent. Bengal's trade and wealth impressed the Mughals so much that it was described as the Paradise of the Nations by the Mughal Emperors. Under Mughal rule, Bengal was a centre of the worldwide muslin, the silk trades and of cotton production, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka. Muslin was called "daka" in distant markets as far as Central Asia. Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and even opium; Bengal accounted for sourcing 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks. Saltpetre was also shipped to Europe, opium was sold in Indonesia, raw silk was exported to Japan and the Netherlands, cotton and silk textiles were exported to Europe, Indonesia, and Japan, and cotton cloth was exported to the Americas and the region surrounding the Indian Ocean. Bengal also had a large shipbuilding industry. In terms of shipbuilding tonnage during the 16th–18th centuries, economic historian Indrajit Ray estimates the annual output of Bengal at 223,250 tons, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771 (Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. p. 174.).

A Dutch map of 1638 showing Bengal, Chittagong and Arakan

During the 16th century, European traders navigated their way along the sea routes to Bengal, subsequent to the Portuguese conquests of Malacca and Goa. The Portuguese had established a settlement in Chittagong with permission from the Bengal Sultanate in 1528, but were later expelled by the Mughals in 1666. In the 18th-century, the Mughal Court rapidly disintegrated due to Nader Shah's invasion and internal rebellions, allowing European colonial powers to set up trading posts across the territory. The British East India Company eventually emerged as the foremost military power in the region; and defeated the last independent Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. This was a decisive victory of the British East India Company over the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies on 23 June 1757, under the leadership of Robert Clive. The victory was made possible by the defection of Mir Jafar, who was Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah's commander in chief. The battle helped the British East India Company take control of Bengal. Over the next hundred years, they seized control of most of the rest of the Indian subcontinent, Burma, and Afghanistan.

Painting by Francis Hayman (1708–1776) of Lord Clive meeting with Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey

In the section on the Colonial era (1757-1947) in the Wikipedia article on Bengal begins with this paragraph:

In Bengal effective political and military power was transferred from the old regime to the British East India Company around 1757–65.Company rule in India began under the Bengal Presidency. Calcutta was named the capital of British India in 1772. The presidency was run by a military-civil administration, including the Bengal Army, and had the world's sixth earliest railway network. Great Bengal famines struck several times during colonial rule (notably the Great Bengal famine of 1770 and (the) Bengal famine of 1943).

So, both the beginning and the end of British colonial rule are marked by great famines, while approximately 50 million died in Bengal, mostly in western Bengal, as a result of massive plague outbreaks and a succession of famines during the period 1895 to 1920. To quote from an online article by J. M. Opal on the Commonplace website, referencing the ideas of the pamphleteer, activist and revolutionary, Thomas Paine and his pamphlet Common Sense:

Paine was deeply influenced by imperial misdeeds, not only in North America, where he arrived late in 1774, but also in South Asia. At a crucial moment in his life and career, just before his trip to America, he came upon a set of atrocities committed by British soldiers and fortune seekers in Bengal and Bihar—what is now eastern India and Bangladesh. These crimes against people on the eastern fringes of British rule seared dreadful images into his mind, images that he then relayed to people on its western margins. Mass shootings, plunder, famine—this is what Thomas Paine came to know of South Asia’s recent past and to expect of North America’s near future.

J. M. Opal comments further on the British "takeover" of Bengal:

The collapse of Mughal rule and the onset of civil government by a for-profit corporation made an ideal milieu for corruption, venality, and violence. Failed rains in late 1769 and 1770 triggered severe hunger in Bengal, and when company agents disrupted both the production and distribution of rice—in some cases profiting from the sudden spike in the price of calories—crisis turned into catastrophe. Several million people perished. Witnesses spoke of bodies clogging the streets, contaminating the rivers, and satiating the birds and rodents. In testimony to Parliament in May 1772, Major Hector Munro discussed his handling of a mutiny among the native soldiers, or sepoys, serving under him eight years before. Four at a time, the mutineers were marched to the front of his assembled troops, tied to the mouths of cannon, and “blown away.” In all, twenty-four sepoys went up in gun smoke and gore. None of Munro’s listeners in Parliament questioned these tactics, although they did wonder about his pay. One even noted the “merit” of his service.

The deindustrialisation of Bengal and the financing of the industrial revolution in England

The transformation of Bengal from a highly productive hive of industry to a predominantly rural economy following the Battle of Plassey was instigated by the British in their twofold policy of a decapitalisation of the state of Bengal and the use of domestic tariff barriers to effect a discriminatory impact upon Bengali industries. Meanwhile the silver that flowed from Bengal and arrived in England provided the Bank of England with the financial leverage that financed and enabled the British industrial revolution.

The burning of coal in England's new industrial heartlands and the resulting release of carbon into the world's atmosphere begins a process of industrially sourced pollution that has increased exponentially to this day.

This is a familiar narrative that has been politicised for many in India and Bangladesh. For example this article by Saquib Salim (published 23 June 2021) How Bengal financed industrial revolution after Battle of Plassey on the multi media digital platform Awaz-The Voice (committed to the idea of an inclusive India, with an aim of promoting the inherent strengths of a pluralistic Indian ethos - an against the policy of divide and rule):

23 June, 1757, is a landmark date in the history of the world in general and the history of India in particular.On this day forces of the English East India Company decisively defeated a much larger force of Nawab of Bengal, thus paving the way for the direct political control of India. Nawab of Bengal, Siraj Ud-Daulah, faced defeat at the hands of Robert Clive. More than superior militaristic abilities and courage, the reason for the English victory was treachery by Nawab’s officials like Mir Jafar and Rai Durlab. The result of this battle had far-reaching consequences much beyond the geographical boundaries of Bengal or the time period.

Several historians and economists like Brooke Adams, Victoria Miroshnik, Dipak Basu etc. have pointed out that the industrial revolution, which changed the world we live in forever, was in fact fuelled by the money plundered from Bengal by the English after the battle of Plassey in 1757. Industrial revolution is an umbrella term used for the developments leading to mechanisation of the factory production system in Europe since 1760. A number of inventions and discoveries were made especially to mechanize the textile industry in England around this time.Historian R.P Dutt argues that it was the exploitation of Bengal after 1757 which provided for the necessary finances required to fund the various researches and production in England resulting in the advent of industrial revolution. According to estimates, the English remitted 1 billion Pounds from Bengal as damage of war after the battle. The extent of loot can be gauged from the fact that each subaltern (foot soldier) of the English East India Company received 3,000 Pounds after the war. To put in perspective, the highest officials in London would not get more than 800 Pounds a year as salary at that time.After their ‘victory’ in 1757, the Company officials started extorting money from the rulers, landlords, merchants and common men. During the next eight years, they extorted 6 million Pounds annually, which was four times the total land revenue of Bengal. In 1765, the Company took direct revenue collection rights for themselves. A rather conservative estimate puts their annual remittance from Bengal to be at 22 million Pounds.Indian Nationalist leader Dadabhai Naoroji in his book ‘Poverty and Un-British Rule in India’ (1880) noted,“It is not the pitiless operations of economic laws, but it is thoughtless and pitiless action of the British policy; it is pitiless eating of India’s substance in India and further pitiless drain to England, in short it is pitiless perversion of Economic Laws by the sad bleeding to which India is subjected, that is destroying India.”England was investing a considerable proportion of its revenue into industrial developments through research and infrastructure building. It is no coincidence that “the inventions between 1764 and 1785 were the spinning jenny by Hargreaves, the water frame by Arkwright, the mule by Crompton, and the power-loom by Cartwright. John Kays had invented the flying shuttle and coal began to replace wood in smelting, while in 1768 Watt matured the steam engine.”Today, Europe claims its superiority on the basis of advancements of the same institutions which were made from the blood of our forefathers and foremothers.

Bengali ethnicity, religious and and ethnic driven prejudice and the legacy of the British "Divide and Rule" policy

An Al Jazeera feature on Racism looks at the plight of Bengali origin people in the Indian state of Assam.

There is a section in this article by Saif Khalid (23 June 2018) on the colonial legacy that is as pernicious as it is corrupt.

Indigenous versus the outsiders

Assam is home to 32 million people – one-third of them are Muslim, most of them Bengali origin. The first arrival of Bengali cultivators began in the 19th century after British colonial rulers took over Assam from the Ahom king in 1826. Back then, Assam was sparsely populated with dense jungles. In 1855, an English military officer, Major John Butler, called Assam a “dreary and desolate wilderness … devoid of man, beasts, or birds”.

By the early 20th century, millions of Bengali people were settled in Assam, as part of the British policy. The fertile land of Assam attracted people not only from Bengal but also from Bihar and Odisha states. The policy of bringing more Bengali immigrants by the government of Sayed Mohammad Sadullah in the 1930s as part of its “Grow More Food” programme further polarised Assam’s politics on the issue of indigenous versus the outsiders.

CS Mullan, superintendent of the 1931 Assam Census, likened Bengali immigrants to “an invading, conquering army, to a terrifying birds of prey, and to insects”. For Mullan, an Indian civil service officer, Bengali immigrants were like “vultures” looking to grab lands. “The motivation behind such irresponsible and utterings was clear. He wanted the Assamese and the immigrants to be set against each other,” wrote academic Amalendu Guha in his book, “Planter Raj to Swaraj”.

After India’s independence in 1947, more than 200,000 Bengali people were deported to what was then East Pakistan under the Prevention of Infiltration from Pakistan scheme. Author Rizwana Shamshad wrote in her book, “Bangladeshi Migrants in India: Foreigners, Refugees, or Infiltrators?”, that a narrative was built around Bengali origin people as “land grabbers” and “settlers” against ethnic Assamese depicted as “vulnerable”.

Colonial role overlooked

The dominant narrative in Assam has overlooked the colonial role in bringing immigrants to Assam. Sushanta Talukdar, a senior journalist in Guwahati, said the media helped “perpetuate the stereotype about the community”.

“The fear [of undocumented immigrants] was real, but it was amplified by the media,” he said. “We cannot deny that there is no problem, but media should have played a responsible role in finding out facts and instead of being carried away by the agenda of the political parties.”

India’s Supreme Court quoted Mullan in its 2003 judgement, when it scrapped a controversial tribunal, the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act (IMDT), set up in 1983 to try suspected foreigners. Assam politicians had demanded the repeal of the IMDT Act, under which the burden of proof was on the state. “The SC brought back foreigners Act 1946, a British era law, under which the burden of proof shifted to suspects,” Wadud said, adding that it is against natural justice.

Islam of the AIUDF party says the agenda over who is a foreigner has gradually changed over the years. “In the 1970s, they said remove outsiders, including Indians from other states. Then they said remove foreigners, including Nepalis and Bangladeshis,” Haque said. “Now they are saying exempt Bengali Hindus and deport Bengali origin Muslims. From outsiders it has come down to just Muslims. It’s a secular state, rules should be applied equally to all.”

The sons of the soil

Among those of Bengali origin, such as Suleman Qasimi from Nellie village, there is a belief that people who have harmed and killed Muslims have enjoyed impunity. “We are bhumiputra, the son of the soil. Do not call us Bangladeshis, we are Indians,” he said, anger palpable on his face. His brother was among the nearly 2,000 people massacred in 1983 in his village during the height of anti-Bengali movement. “[Until now], no one has been charged for the carnage, except for a compensation of 5,000 rupees ($73),” said Qassemi, who is the leader of a local mosque. “Muslims were killed because they voted in defiance of the election boycott called by the protesters. My brother died for democracy,” he said, claiming that those who harassed and killed Muslims during the Assam Movement have been rewarded.

In 2016, the BJP government in the state announced compensation of 500,000 rupees ($7,345) to the more than 800 killed during the anti-Bengali Assam agitation. But successive Congress governments, Qasimi said, did nothing to provide justice to the victims. Organisations and political groups such as All Assam Students Union (AASU), which led the Assam agitation between 1979-85, have played on the fear of undocumented immigrants. “The problem is that the BJP is creating a fear psychosis that Muslim population is growing by leaps and bounds and they are going to swamp the local indigenous population,” Assam Congress leader Prodyut Bordoloi said. He said that the migration from Bangladesh has “almost stopped in the past 25 to 30 years”.

Muslims have been well represented in the state Assembly with 30 members from the community in the 126-seat state assembly, but they are at the bottom of development indices. The community suffers from mass illiteracy and poverty while the fear of being branded foreigners persists.

Assimilated into Assamese society

Hafiz Ahmed, a Guwahati-based Bengali-origin Muslim and activist, says that Muslims face discrimination and harassment despite having living in the state for generations. “My grandfather came to Assam … We do not need any certificate that we are Assamese,” he said. “Muslims have contributed a lot to the Assamese language and culture. And they have always wanted to be assimilated with the greater Assamese nationality.”

The 54-year-old started writing Miya poetry to express the anguish and pain at the way the community has been treated. “Miyan means gentleman but here it is used in a derogatory manner to refer to Bengali origin people,” he said. “Miya poetry is a voice against injustice and discrimination. For the first time we have seen that some young people from the community have come out. They have used literature as a means of protest.”

Kazi Neel is one among the young protesters from the community who has picked up a pen.

The land that makes my father an alien

That kills my brother with bullets

My sister with gang-rape

The land where my mother stokes in heart live burning coals

That land is mine

I am not of that land

The land where limb after limb is chopped and sent afloat the river

Where in 1983, the executioners danced a shameless grisly dance of celebration

That land is mine

I am not of that land

The land where my homes and hearths is uprooted

Where my heritage is negated

Where they conspire to bind me forever in darkness

Where they pour gravel, not gruel on my plate

That land is mine

I am not of that land

The land where my throat cracks with appeals and no one hears

Where my blood flows cheap and no one pays

Where they do politics over my son’s coffin

And gamble with my daughter’s honour

The land where I wander crazy, confused as a beast

That land is mine

I am not of that land

[Poem originally written in Miya dialect by Kazi Neel. Translated into English by Shalom M Hussain]

Kazi Neel writes poetry in Miya dialect and also teaches children from the community

The anthropogenic causes of famine in Bengal during 1943

In the colonial history of India the effective, or more accurately stated, ineffective policy of Winston Churchill's War Cabinet in regard to the Bengal famine of 1943, contributed to the beginning of the end of British colonial rule.The Bengal famine of 1943 was a famine in the Bengal province of British India during World War II. An estimated 2,100,000 to 3,000,000 lives that apparently did NOT matter, were lost during this man made disaster, out of a population of 60.3 million. They died of starvation, malaria, or other diseases aggravated by malnutrition, population displacement, unsanitary conditions and lack of health care, and imperial policy. Millions were impoverished as the crisis overwhelmed large segments of the economy and catastrophically disrupted the social fabric. Eventually, families disintegrated; men sold their small farms and left home to look for work or to join the British Indian Army, and women and children became homeless migrants, often travelling to Calcutta or other large cities in search of organised relief. Historians usually characterise the famine as anthropogenic (man-made), asserting that wartime colonial policies created and then exacerbated the crisis.

Beginning as early as December 1942, high-ranking government officials and military officers including, John Herbert, the Governor of Bengal; Viceroy Linlithgow; Leo Amery the Secretary of State for India; General Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in India, and Admiral Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Commander of South-East Asia, began requesting food imports for India through government and military channels, but for months these requests were either rejected or reduced to a fraction of the original amount by Churchill's War Cabinet. The colony was also not permitted to spend its own sterling reserves, or even use its own ships, to import food. Although Viceroy Linlithgow appealed for imports from mid-December 1942, he did so on the understanding that the military would be given preference over civilians. The Secretary of State for India, Leo Amery, was on one side of a cycle of requests for food aid and subsequent refusals from the British War Cabinet that continued through 1943 and into 1944. Amery did not mention worsening conditions in the countryside, stressing that Calcutta's industries must be fed or its workers would return to the countryside. Rather than meeting this request, the UK promised a relatively small amount of wheat that was specifically intended for western India (that is, not for Bengal) in exchange for an increase in rice exports from Bengal to Ceylon.

The tone of Linlithgow's warnings to Amery grew increasingly serious over the first half of 1943, as did Amery's requests to the War Cabinet; on 4 August 1943 Amery noted the spread of famine, and specifically stressed the effect upon Calcutta and the potential effect on the morale of European troops. The cabinet again offered only a relatively small amount, explicitly referring to it as a token shipment. The explanation generally offered for the refusals included insufficient shipping, particularly in light of Allied plans to invade Normandy. The Cabinet also refused offers of food shipments from several different nations. When such shipments did begin to increase modestly in late 1943, the transport and storage facilities were understaffed and inadequate. When Viscount Archibald Wavell replaced Linlithgow as Viceroy in the latter half of 1943, he too began a series of exasperated demands to the War Cabinet for very large quantities of grain. His requests were again repeatedly denied, causing him to decry the current crisis as "one of the greatest disasters that has befallen any people under British rule, and [the] damage to our reputation both among Indians and foreigners in India is incalculable". Churchill wrote to Franklin D. Roosevelt at the end of April 1944 asking for aid from the United States in shipping wheat in from Australia, but Roosevelt replied apologetically on 1 June that he was "unable on military grounds to consent to the diversion of shipping".

Experts' disagreement over political issues can be found in differing explanations of the War Cabinet's refusal to allocate funds to import grain. Lizzie Collingham holds the massive global dislocations of supplies caused by World War II virtually guaranteed that hunger would occur somewhere in the world, yet Churchill's animosity and perhaps racism toward Indians decided the exact location where famine would fall. Similarly, Madhusree Mukerjee makes a stark accusation: "The War Cabinet's shipping assignments made in August 1943, shortly after Amery had pleaded for famine relief, show Australian wheat flour travelling to Ceylon, the Middle East, and Southern Africa – everywhere in the Indian Ocean but to India. Those assignments show a will to punish." In contrast, Mark Tauger strikes a more supportive stance: "In the Indian Ocean alone from January 1942 to May 1943, the Axis powers sank 230 British and Allied merchant ships totalling 873,000 tons, in other words, a substantial boat every other day. British hesitation to allocate shipping concerned not only potential diversion of shipping from other war-related needs but also the prospect of losing the shipping to attacks without actually [bringing help to] India at all."Michael Safi in Delhi reporting for the Guardian (Fri 29 Mar 2019) under the headline and subheading:Churchill's policies contributed to 1943 Bengal famine – study

Study is first time weather data has been used to argue wartime policies exacerbated famineMichael Safi writes:The Bengal famine of 1943 was the only one in modern Indian history not to occur as a result of serious drought, according to a study that provides scientific backing for arguments that Churchill-era British policies were a significant factor contributing to the catastrophe.Researchers in India and the US used weather data to simulate the amount of moisture in the soil during six major famines in the subcontinent between 1873 and 1943. Soil moisture deficits, brought about by poor rainfall and high temperatures, are a key indicator of drought.

Five of the famines were correlated with significant soil moisture deficits. An 11% deficit measured across much of north India in 1896-97, for example, coincided with food shortages across the country that killed an estimated 5 million people.

However, the 1943 famine in Bengal, which killed up to 3 million people, was different, according to the researchers. Though the eastern Indian region was affected by drought for much of the 1940s, conditions were worst in 1941, years before the most extreme stage of the famine, when newspapers began to publish images of the dying on the streets of Kolkata, then named Calcutta, against the wishes of the colonial British administration.Media coverage of the 1943 Bengal famine

Calcutta's two leading English-language newspapers were The Statesman (at the time British-owned) and Amrita Bazar Patrika (edited by independence campaigner Tushar Kanti Ghosh). In the early months of the famine, the government applied pressure on newspapers to "calm public fears about the food supply" and follow the official stance that there was no rice shortage. This effort had some success; The Statesman published editorials asserting that the famine was due solely to speculation and hoarding, while "berating local traders and producers, and praising ministerial efforts". News of the famine was also subject to strict war-time censorship – even use of the word "famine" was prohibited – leading The Statesman later to remark that the UK government "seems virtually to have withheld from the British public knowledge that there was famine in Bengal at all".

Beginning in mid-July 1943 and more so in August, however, these two newspapers began publishing detailed and increasingly critical accounts of the depth and scope of the famine, its impact on society, and the nature of British, Hindu, and Muslim political responses.

A turning point in news coverage came in late August 1943, when the editor of The Statesman, Ian Stephens, solicited and published a series of graphic photos of the victims. These images made world headlines.

Dead or dying children on a Calcutta Street

This publication marked the beginning of domestic and international consciousness of the famine. The next morning, "in Delhi second-hand copies of the paper were selling at several times the news-stand price," and soon "in Washington the State Department circulated them among policy makers". In Britain, The Guardian called the situation "horrible beyond description". The images had a profound effect and marked "for many, the beginning of the end of colonial rule". Stephens' decision to publish them and to adopt a defiant editorial stance won accolades from many,including the Famine Inquiry Commission, and has been described as "a singular act of journalistic courage without which many more lives would have surely been lost". The publication of the images, along with Stephens' editorials, not only helped to bring the famine to an end by driving the British government to supply adequate relief to the victims, but also inspired Amartya Sen's influential contention that the presence of a free press prevents famines in democratic countries.

The photographs also spurred Amrita Bazar Patrika and the Indian Communist Party's organ, People's War, to publish similar images; the latter would make photographer Sunil Janah famous.Women journalists who covered the famine included Freda Bedi reporting for Lahore's The Tribune, and Vasudha Chakravarti and Kalyani Bhattacharjee, who wrote from a nationalist perspective.A contemporary sketchbook of iconic scenes of famine victims, Hungry Bengal: a tour through Midnapur District in November, 1943 by Chittaprosad, was immediately banned by the British and 5,000 copies were seized and destroyed. One copy was hidden by Chittaprosad's family and is now in the possession of the Delhi Art Gallery.Post-colonial systemic racism? Pakistan's systemic economic, ethnic and linguistic discrimination against East Bengal

Bengal was eventually divided during the partition of India into the state West Bengal, as part of India, and East Bengal as part of Pakistan. Then in 1971 Pakistan was separated from East Bengal in its own civil war that led to the independence of East Bengal and the formation of a new nation, Bangladesh. The background to this conflict stemmed from Pakistan's systemic economic discrimination against East Bengal. According to senior World Bank officials, the Pakistani government practised extensive economic discrimination against East Pakistan: greater government spending on West Pakistan, financial transfers from East to West Pakistan, the use of East Pakistan's foreign-exchange surpluses to finance West Pakistani imports, and refusal by the central government to release funds allocated to East Pakistan because the previous spending had been under budget; though East Pakistan generated 70 percent of Pakistan's export revenue with its jute and tea. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested for treason in the Agartala Conspiracy Case and was released during the 1969 uprising in East Pakistan which resulted in Ayub Khan's resignation. General Yahya Khan assumed power, reintroducing martial law.Ethnic and linguistic discrimination was common in Pakistan's civil and military services, in which Bengalis were under-represented. Fifteen percent of Pakistani central-government offices were occupied by East Pakistanis, who formed 10 percent of the military. Cultural discrimination also prevailed, making East Pakistan forge a distinct political identity. Authorities banned Bengali literature and music in state media, including the works of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore. A cyclone devastated the coast of East Pakistan in 1970, killing an estimated 500,000 people, and the central government was criticised for its poor response. After the December 1970 elections, calls for the independence of East Bengal became louder; the Bengali-nationalist Awami League won 167 of 169 East Pakistani seats in the National Assembly. The League claimed the right to form a government and develop a new constitution but was strongly opposed by the Pakistani military and the Pakistan Peoples Party led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

The Bengali population was angered when Prime Minister-elect Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was prevented from taking the office. Civil disobedience erupted across East Pakistan, with calls for independence. The Prime Minister-elect addressed a pro-independence rally of nearly 2 million people in Dacca (as Dhaka used to be spelled in English) on 7 March 1971, where he said, "This time the struggle is for our freedom. This time the struggle is for our independence." The flag of Bangladesh was raised for the first time on 23 March, Pakistan's Republic Day.

The iconic speech delivered by the father of the nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on 7 March 1971 has been recognised by UNESCO as a part of the ‘Memory of the World Register’ as a documentary heritage. It is an integral part of the history of independent Bangladesh.

Museum of Independence, Dhaka

A forgotten war and a forgotten genocide?

Later, on 25 March late evening, the Pakistani military junta led by Yahya Khan launched a sustained military assault on East Pakistan under the code name of Operation Searchlight.

Operation Searchlight: The location of Pakistani and Bengali units on 25 March 1971.

The Pakistan Army arrested Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and flew him to Karachi. However, before his arrest Mujib proclaimed the Independence of Bangladesh at midnight on 26 March which led the Bangladesh Liberation War to break out within hours. The Pakistan Army and its local supporters continued to massacre Bengalis, in particular students, intellectuals, political figures, and Hindus in the 1971 Bangladesh genocide.

During the nine-month-long Bangladesh Liberation War, members of the Pakistan Armed Forces and supporting pro-Pakistani Islamist militias from Jamaat-e-Islami killed between 300,000 and 3,000,000 people and raped between 200,000 and 400,000 Bengali women, in a systematic campaign of genocidal rape. The Government of Bangladesh states 3,000,000 people were killed during the genocide, making it the largest genocide since the Holocaust during World War II.

The actions against women were supported by Pakistan's religious leaders, who declared that Bengali women were gonimoter maal (Bengali for "public property"). As a result of the conflict, a further eight to ten million people fled the country to seek refuge in neighbouring India. It is estimated that up to 30 million civilians were internally displaced out of 70 million. During the war, there was also ethnic violence between Bengalis and Urdu-speaking Biharis. Biharis faced reprisals from Bengali mobs and militias, and with wildly varying estimates of those killed running from 1,000 to 150,000, who knows how many were killed.

Rivers of death?

The rivers and waterways of East Bengal give up some of the victims of the 1971 Bangladesh genocide. There is an academic consensus that the events which took place during the Bangladesh Liberation War constituted a genocide; however, there are some scholars and authors who disagree. The Mukti Bahini, a guerrilla resistance force, also violated human rights during the conflict. During the war, there are wide estimates as to how many deaths were involved ranging from an estimated 0.3 to 3.0 million people. Several million people had to find shelter in neighbouring India.

From Midnight's Children to Heart of Darkness

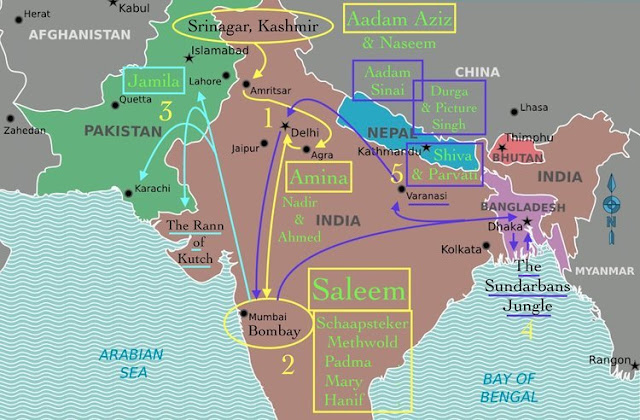

This map of charts the five main episodes along with their settings in the 1981 novel Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie.

1. The early years under the British, including the Amritsar Massacre of 1919 and the struggles leading to Partition

2. The British leave India in 1947

3. Pakistan slides from democratic rule, and engages in war with India

4. Pakistan's civil war leads to the state of Bangladesh

5. In Delhi, Indira Gandhi suspends parliament during The Emergency of 1975-77, shaking confidence in Indian democracy; some citizens are sterilized

The character Saleem in Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children, is born precisely at midnight, 15 August 1947, therefore, exactly as old as independent India. He later discovers that all children born in India between 12 a.m. and 1 a.m. on that date are imbued with special powers. Saleem, using his telepathic powers, assembles a Midnight Children's Conference, reflective of the issues India faced in its early statehood concerning the cultural, linguistic, religious, and political differences faced by a vastly diverse nation. Saleem acts as a telepathic conduit, bringing hundreds of geographically disparate children into contact while also attempting to discover the meaning of their gifts. In particular, those children born closest to the stroke of midnight wield more powerful gifts than the others. Shiva "of the Knees", Saleem's nemesis, and Parvati, called "Parvati-the-witch," are two of these children with notable gifts and roles in Saleem's story.

Saleem moves with his entire family to Pakistan after India’s military loss to China. His younger sister, now known as Jamila Singer, becomes the most famous singer in Pakistan. Already on the brink of ruin, Saleem’s entire family — save Jamila and himself — dies in the span of a single day during the war between India and Pakistan. During the air raids, Saleem gets hit in the head by his grandfather’s silver spittoon, which erases his memory entirely. Relieved of his memory, Saleem is reduced to an animalistic state. He finds himself conscripted into military service, as his keen sense of smell makes him an excellent tracker. Though he doesn’t know exactly how he came to join the army, he suspects that Jamila sent him there as a punishment for having fallen in love with her. While in the army, Saleem helps quell the independence movement in Bangladesh. After witnessing a number of atrocities, however, he flees into the jungle with three of his fellow soldiers. In the jungle of the Sundarbans, he regains all of his memory except the knowledge of his name. The nightmarish aspects of the jungle resonate with the racist and colonialist paranoia experienced while navigating on the rivers featured in Conrad's The Heart of Darkness and Coppola's Apocalypse Now.

The Thames and the Congo merge at Gravesend

In the 1902 novel Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad has Marlow/Conrad the narrator talking with others on a ship moored on the dark aired River Thames at Gravesend. This river, a river at the heart of the British Empire is the setting from which Marlow begins his reminiscences and then tells his tale.

Foggy Morning on the Thames – James Hamilton

Steve McQueen’s film Gravesend (2007) is concerned with the mining of coltan, a dull black mineral used in capacitors, which are vital components in mobile phones, laptops, and other electronics. Juxtaposing an animated fly-by of the Congo River with footage of workers sifting through dark earth and robots processing the procured material in a pristine, brightly lit laboratory, the film’s disjunctions allegorise the very real economic, social and physical distance this material traverses as it moves from the third to the first world. Its final sequence, a time-lapse shot of a sun setting behind smokestacks, brings everything full circle, rendering visual a scene described at the outset of Joseph Conrad’s celebrated novel, Heart of Darkness.

Maya Jasanoff writes of Conrad and this novel in her book The Dawn Watch:

Heart of Darkness remains one of the most widely read novels in English; and the movie adaptation Apocalypse Now has brought Conrad's story to still more. The very phrase has taken on a life of its own. Conrad's book has become a touchstone for thinking about Africa and Europe, civilization and savagery, imperialism, genocide, insanity - about human nature itself.

It's also about a flash point. In the 1970's, Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe declared Heart of Darkness "an offensive and totally deplorable book," rife with degrading stereotypes of Africa and Africans. Conrad, said Achebe, was "a bloody racist." Not long afterward, a half-American, half-Kenyan college student named Barack Obama was challenged by his friends to explain why he was reading "this racist tract." "Because . . . ," Obama stammered, "because the book teaches me things . . . About white people, I mean. See, the book's not really about Africa. Or black people. It's about the man who wrote it. The European. The American. A particular way of looking at the world."Page 4., The Dawn Watch by Maya Jasanoff

The Congo Basin

European exceptionalism leads to exceptional European brutality!

The author Adam Hochschild deals with the historical background to the Heart of Darkness. The exploitation of the Congo Free State by King Leopold II of Belgium between 1885 and 1908, including the large-scale atrocities committed during that period, are revealed in an exposé of multiple histories conveniently forgotten or suppressed in his bestseller King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa (1998).

Leopold II, King of the Belgians, was fascinated with obtaining a colony and focused upon claiming the interior of Africa — the only unclaimed sizable geographic area. Moving within the European political paradigm existing in the early 1880s, Leopold gained international concessions and recognition for his personal claim to the Congo Free State.

His rule of the vast region was based on tyranny and terror. Under his direction, Stanley again visited the area and extracted favorable treaties from numerous local leaders. A road and, eventually, a rail line were developed from the coast to Leopoldville (present-day Kinshasa). A series of militarized outposts were established along the length of the Congo River, and imported paddle wheelers commenced regular river service. Native peoples were forced to gather ivory and transport it for export. Beginning c. 1890, rubber — originally manufactured from coagulated sap — became economically significant in international trade. The Congo was rich in rubber-producing vines, and Leopold transitioned his exploitative focus from dwindling ivory supplies to the burgeoning rubber market. Slavery, exploitation and the reign of terror continued and even increased.